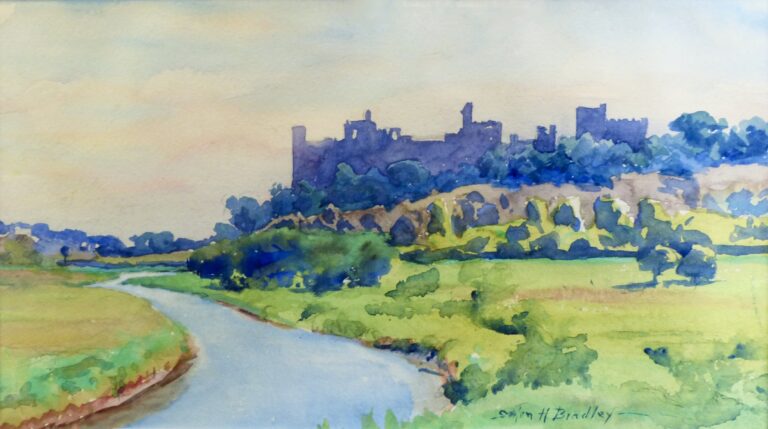

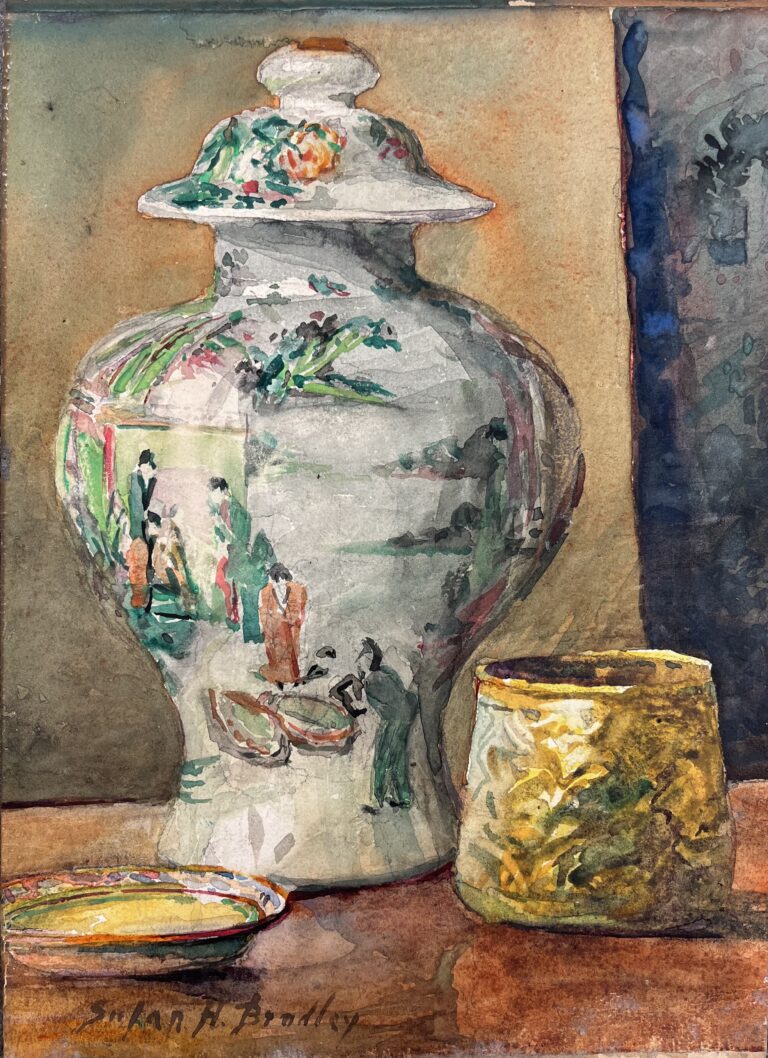

American watercolorist Susan Hinckley Bradley (1851–1929) was a dynamic and influential figure in the art world of her day, although her significance has been largely forgotten by history. Bradley frequently exhibited alongside artist Cecilia Beaux (1855–1942), whose work is represented in NMWA’s collection. The women shared close ties to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) and served on committees related to exhibitions, art education, and public art. New research is uncovering Bradley’s work to elevate the status of women artists and watercolorists alike at a time when male oil painters dominated the art world.

Painting the Town

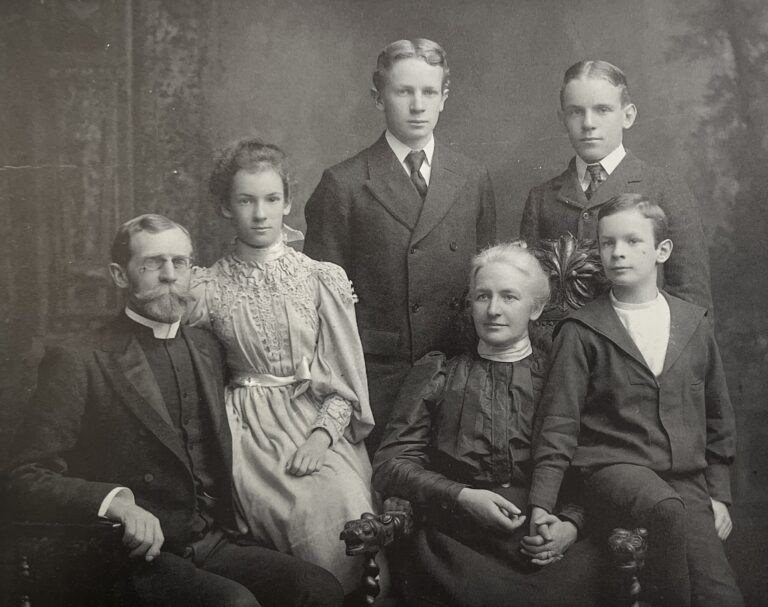

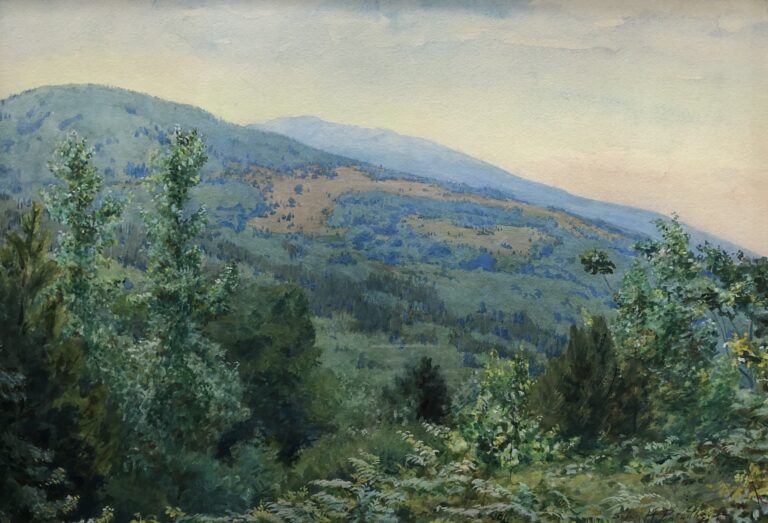

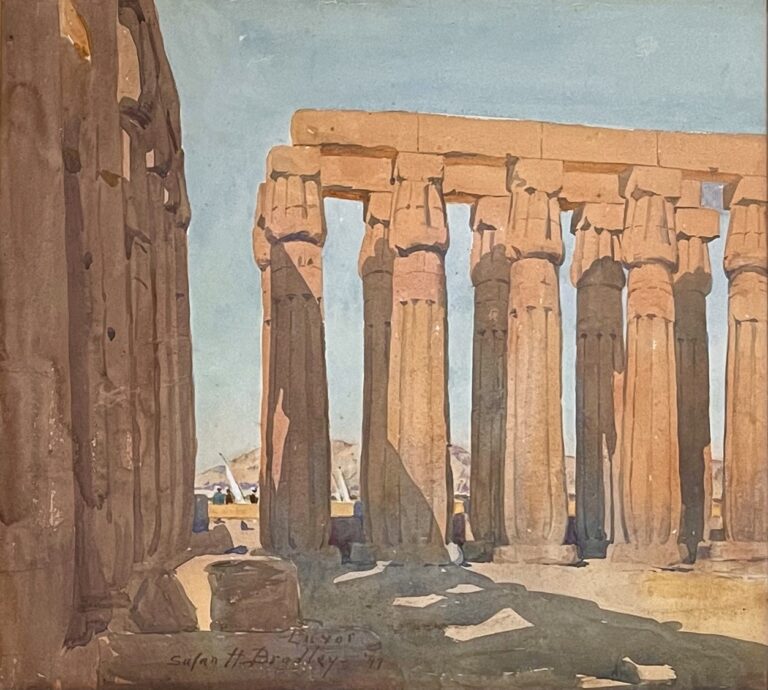

Born in Boston, Bradley was a passionate watercolorist and avid traveler. Many of the watercolors she exhibited in annual exhibitions across America were travel sketches, filled with light, beauty, and a sense of wonder. She portrayed the mountains of New England with the same reverence that she painted the great monuments of ancient Egypt. In 1887, Bradley became a founding member of the Boston Water Color Club. Unlike the Boston Water Color Society, which excluded women, the Boston Water Color Club showcased and promoted the work of women watercolorists who faced fewer exhibition opportunities. Bradley and her four children relocated to Philadelphia in 1888, after her minister husband, Leverett, accepted a new position there. She enrolled in PAFA’s art classes and soon began exhibiting her work throughout the city. In 1897, she helped to found The Plastic Club in Philadelphia (the term “plastic” here refers to the state of an unfinished work of art) and became one of its first vice presidents. The club supported women artists by providing them with a place to meet, exhibit work, and exchange ideas.

The Philadelphia Water Color Club

In 1900, Bradley established the Philadelphia Water Color Club (PWCC) out of her home, along with members of Philadelphia’s artistic elite. According to a 1924 article in the American Magazine of Art, the club aimed to gather support for watercolorists whose work was marginalized in larger exhibitions. PAFA’s annual shows had swelled in size and there were growing concerns over the lack of consideration for watercolor paintings that appeared to be hung in leftover spaces. Though not exclusively a women’s club, women artists were highly represented and made up half of PWCC’s initial membership. Well-respected male professors of art from the University of Pennsylvania and other schools were appointed as the officers, while Bradley maintained a seat on the executive board. In 1904, PAFA joined forces with PWCC to create a second annual exhibition dedicated to watercolors—a monumental achievement for watercolorists.

Bradley was a prolific artist whose career spanned five decades. She exhibited among America’s top artists and her work garnered critical acclaim. Efforts are underway to document Bradley’s life and body of work with the hope of recording and widely sharing her legacy.