Over the course of her nearly six-decade artistic career, Judy Chicago (b. 1939) has published 16 books. The reason she began writing about her work? Because in the 1960s and ’70s, the critics and curators of the male-dominated art world were not.

Familiar as she was with the persistent erasure of women’s achievements throughout history, Chicago was determined to cement her legacy. She committed to growing her artistic skills in service to her creative visions—attending auto body school in the 1960s to learn how to spray paint car hoods; becoming a licensed pyrotechnician for Atmospheres; learning to embroider, blow glass, and cast bronze. She taught and discussed her practice in lectures around the country.

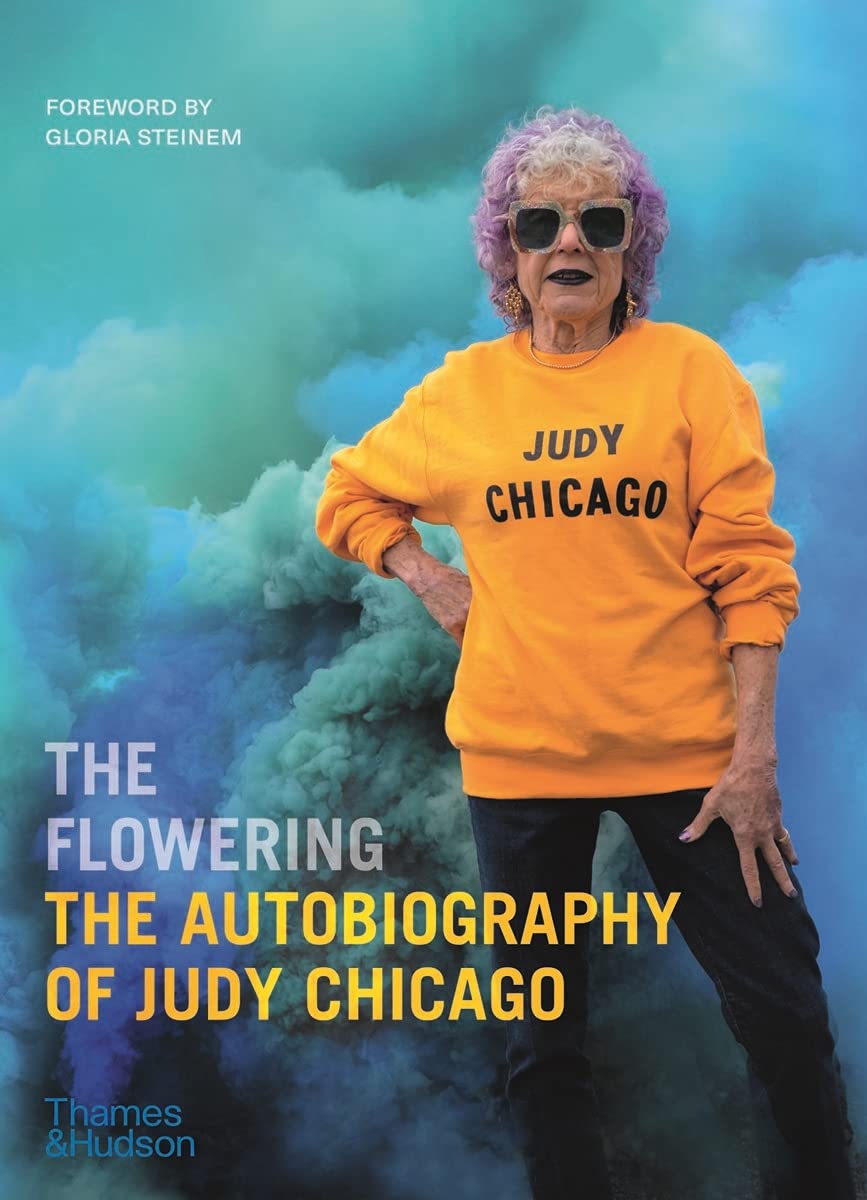

Her prolific output, both artistic and literary, is underscored with the release of The Flowering: The Autobiography of Judy Chicago, published today on the artist’s 82nd birthday. It follows and reflects on her first two autobiographical volumes—and precedes her forthcoming, first-ever career retrospective at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, opening August 28.

The Flowering is a meticulous record of the artist’s life and career—which, for Chicago, are one and the same. As the daughter of progressive Jewish liberals, Chicago witnessed gender equality in her household as a young child. She writes, “I grew up with the sense that I could do what I wanted and be what I wanted.” She wanted to be an artist. Chicago produced finger-painted landscapes at age four; began classes at the Art Institute of Chicago at age five; and decided that she would become a famous artist in grammar school—a pursuit from which she never deviated. Her writing moves fluidly between accounts of her personal life, her artistic endeavors and struggles, and the evolution of her feminism into a feminist art practice.

By now, we know that Judy Chicago became the famous artist she set out to be—and then some. She’s an art-world legend admired for her fierce sense of self. So a notable element of The Flowering is Chicago’s candor about her vulnerabilities, anxieties, and fear. During her 2017 Fresh Talk at NMWA, too, Chicago was praised for her fearlessness, but the artist responded, “I am not fearless. The problem with that perception is that it separates me from everyone else.”

In many ways, this book seeks to reveal Judy Chicago the human, behind the icon. She reflects on hiding her gender in her early minimalist works, dressing to be perceived as masculine, and smoking cigars in an attempt to be accepted by her male peers and professors. She’s had panic attacks, she’s been broke, and she still feels uncertain about the future. She does not want a “triumph over adversity” conclusion to her story. Instead, she writes, “All I can say is that when I am done writing, I will do what I have always done: go back into my studio and try to wrest some meaning from life and the many challenges it presents….”