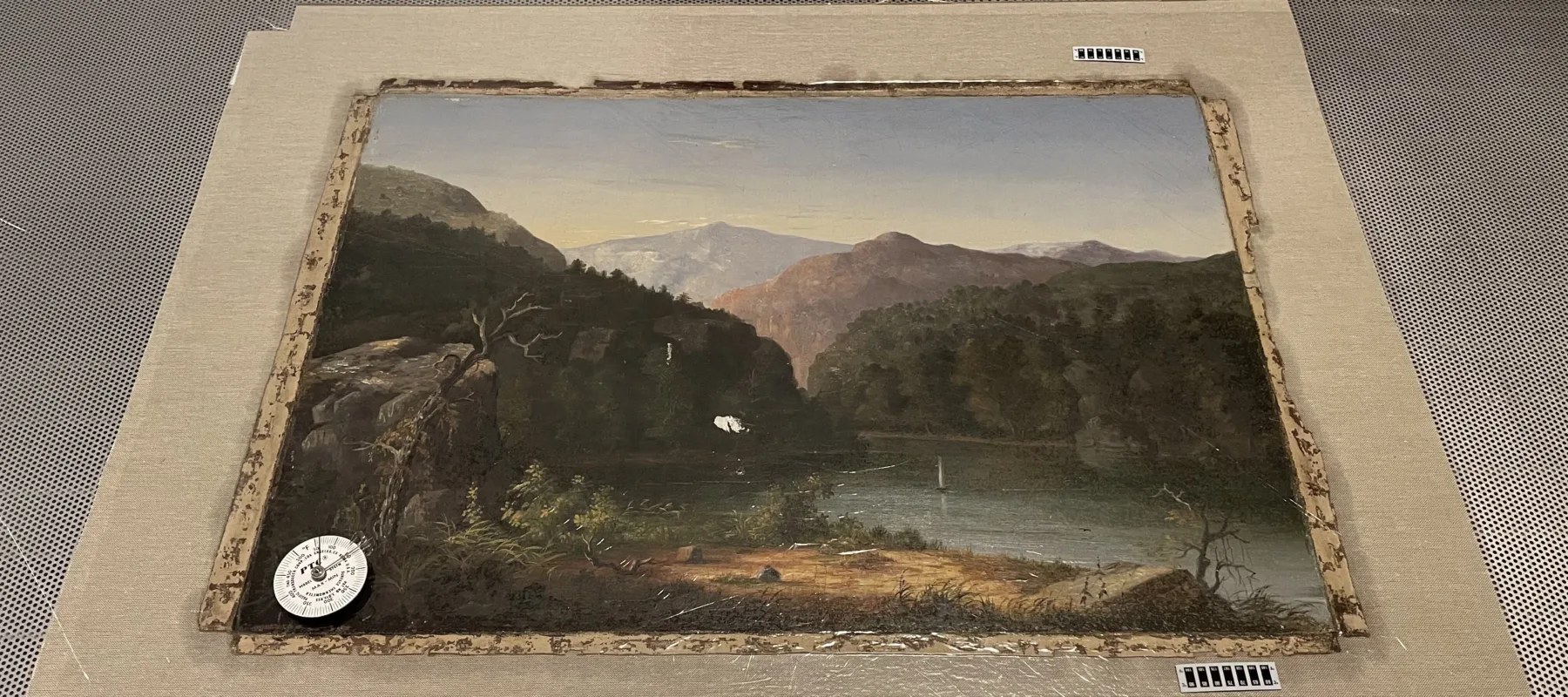

In preparation for NMWA’s reopening in October, two collection works that will be on view for the first time received conservation treatments. Conservator Kristen Loudermilk spent nearly sixty hours with Hudson River Landscape (1852) by Abigail Tyler Oakes (1823–ca. 1898) and Call to Church and Flowers (1970) by Clementine Hunter (1887–1988). With NMWA Assistant Editor Alicia Gregory, she discusses her meticulous work, as well as a few interesting discoveries.

Can you describe the major treatments you carried out for each painting?

Oakes’s painting had previously been lined onto a secondary canvas, which it was separating from. That separation was creating big lumps on this tiny little painting. I don’t usually take linings apart, but in this case, it was warranted because there wasn’t any other way to fix the problem. I used a large tacking iron to gently warm the bulged area, then I left it to cool under weights. This completely resolved the deformations.

I also don’t commonly take off varnishes, but this one had begun to crosslink with the painting’s surface. It almost looked like a layer of plastic. In another twenty or thirty years you might not be able to get it off. For the re-varnish, I used B-72. It has been age-tested in a lab and is very stable. It gave the painting an evenly saturated surface without being too glossy or heavy in appearance.

The Hunter painting came to me because it couldn’t be framed properly—the canvas had been stretched so tight that the top and bottom were bowed inward. The biggest challenge was trying to get that canvas to be on a stretcher with ninety-degree corners. I had to stretch it twice, actually. I used a warm tacking iron to try and reduce the hard creases of the original foldover edge. While this significantly softened the creases, they still are slightly visible at the edges. I’d love to see this painting when it’s framed.

What could you glean about each artist’s technique?

The Oakes painting is just beautiful. Technically, it’s very good. There wasn’t really any evidence, that I could see, of under layers or how she may have laid out the scene. It has a very polished look. There’s also so much texture in it. In the foliage, the foreground, in the rocks and trees. But the sky and water are so nice and smooth. That’s part of what makes the painting so aesthetically beautiful, on such a small scale. I really loved it.

Hunter’s technique on her painting is rock solid. I was initially concerned I would run into trouble as I tried to re-create the edges—that the paint might crack, especially because the trees and grass of her scene are very close to the edge. I had to center it as best as possible and lose as little of the image as possible. But I really didn’t have any trouble. From a conservation perspective, I was very pleased with that.

Were there any surprises in your work?

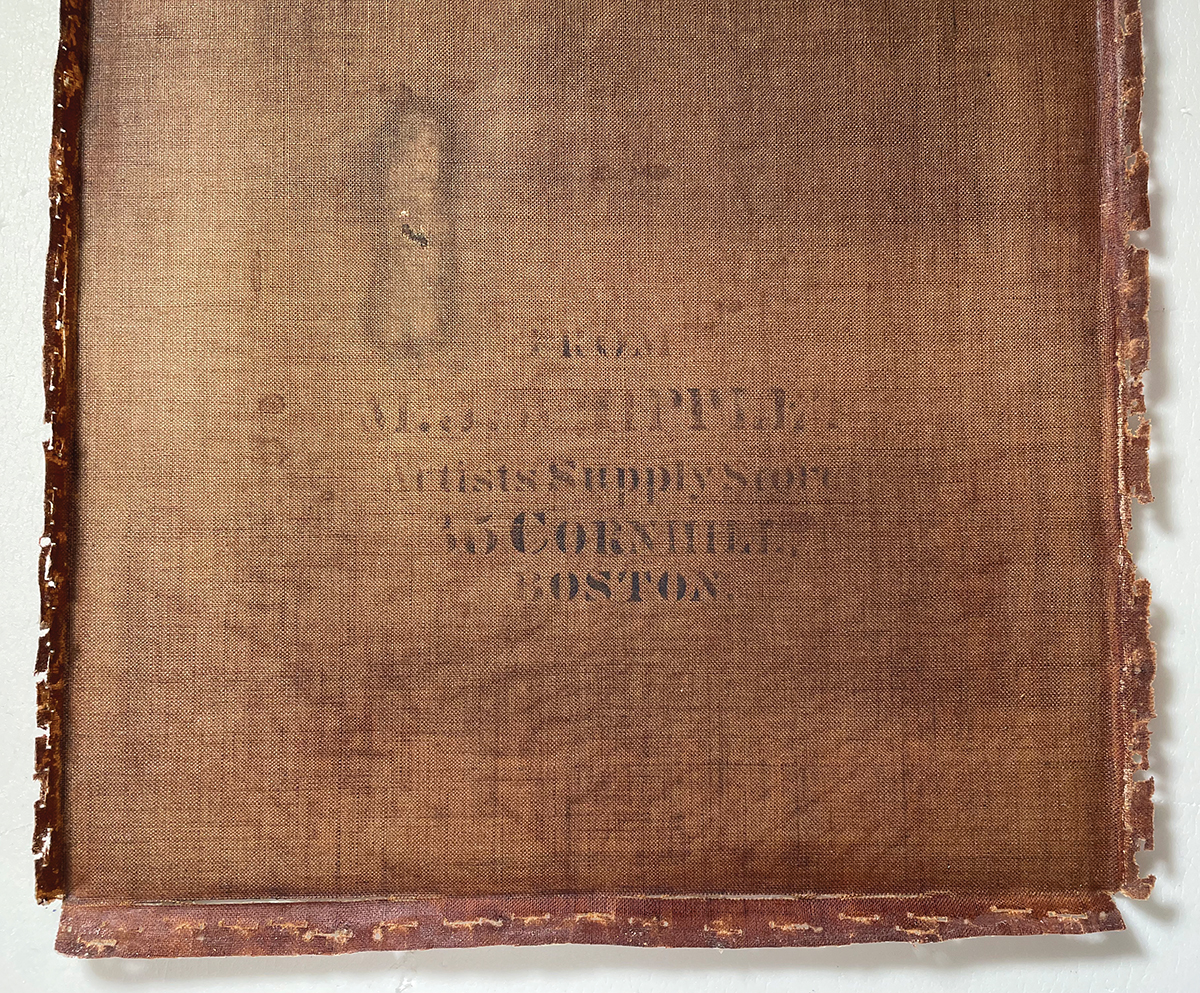

Once I got the lining off of the Oakes painting, I discovered a stamp on the back of the original canvas. It reads, “From / M.J. Whipple’s / Artists Supply Store / 35 Cornhill / Boston.” From this, we can guess that she went to the store in Boston, selected this pre-primed canvas in the size she wanted, and went home—or on location—to paint that beautiful scene. I’d love to know how she did her painting. From memory? In the setting itself?