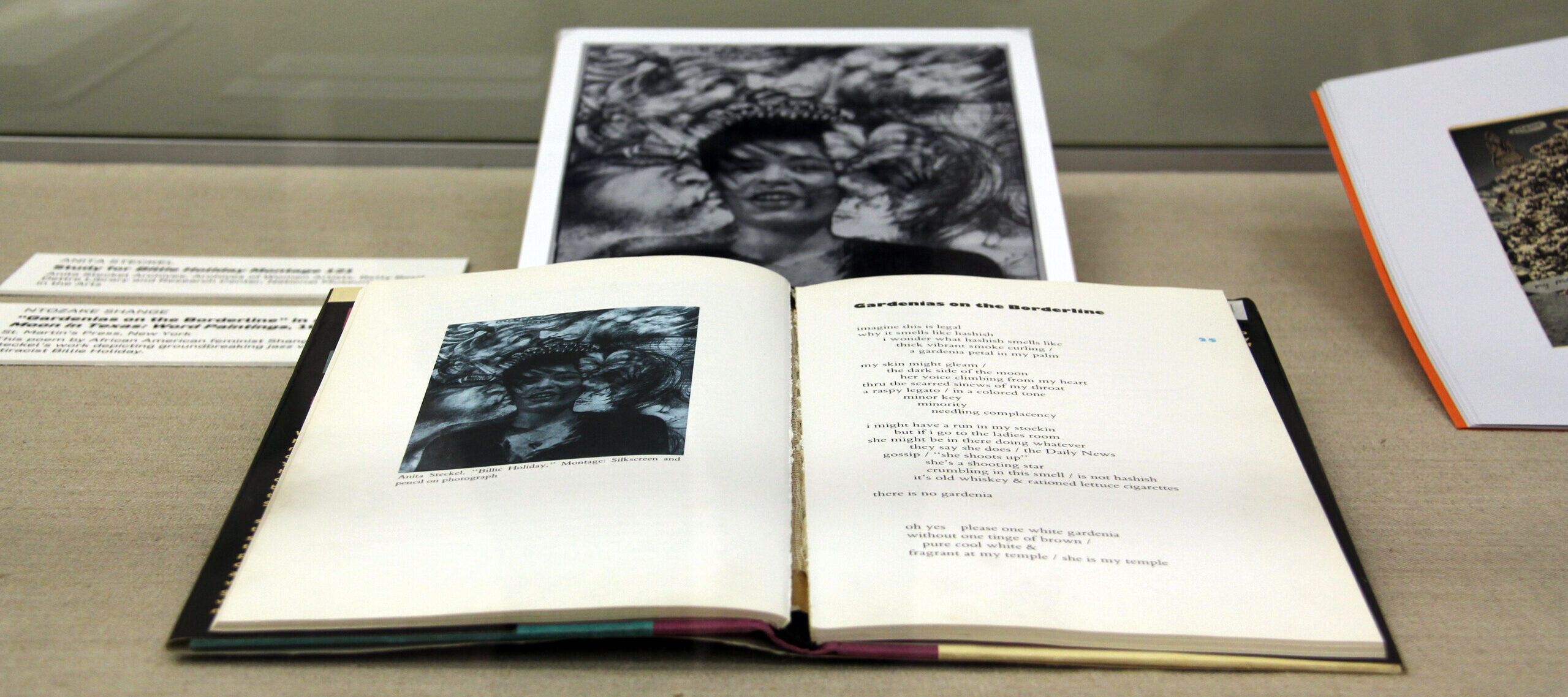

In the 1960s and 1970s, Anita Steckel fought for the public acceptance of explicitly sexual art made by women, as part of the broader feminist art movement that was pushing for a revolution in the gender dynamics that continued to stifle women artists. Steckel’s photo-montages provocatively revamped existing imagery, often adding nudity and references to sexuality in order to vividly convey timely social or political messages.

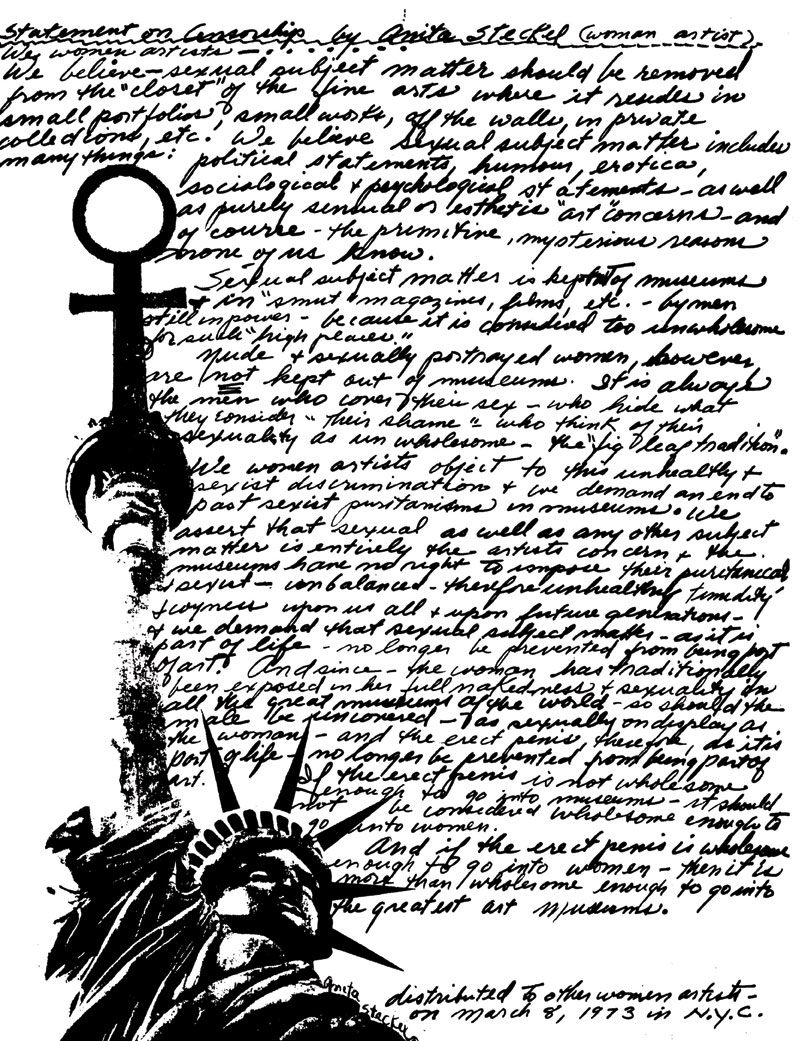

After an exhibition of her work at Rockland Community College was criticized and nearly censored, she formed the Fight Censorship group in 1973, comprising artists who felt that, in Steckel’s words, “sexual subject matter should be removed from the ‘closet’ of the fine arts.”

At the same time, feminist art historians had begun examining the institutional and social structures that prohibited women from becoming professional artists. In the history of Western art, women had traditionally been the models for art while men had been the artists. As historians and critics published new analyses of the ways that the female body had been objectified in art of the past, for some female artists, the pertinent question was how they could represent the human body and sexual experience in a non-objectifying manner.

As Steckel gained a reputation in the 1970s, her work was published in the major feminist art magazines, including Chrysalis, Heresies, The Feminist Art Journal, Off Our Backs, Spare Rib, Womanart, and Women Artists’ News. Despite this critical attention, Steckel’s name had become little known in recent years until art historian Richard Meyer featured her in his essay in the exhibition catalogue for WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution (Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 2007), the first retrospective of the feminist art movement at a major American museum.¹

Although Steckel’s work was not included in the installation, Meyer’s article reintroduced the story of her battle with censorship at Rockland Community College, the Fight Censorship group, and certain feminist artists’ interest in male imagery as representations of both male oppression and female heterosexual desire. Indeed, Steckel’s work was among that which navigated the difficult territory between the pleasure of eroticism and the critique of patriarchal power.

—Rachel Middleman is an assistant professor of art history at Utah State University.

Selections from Steckel’s archive are currently on view in NMWA’s Betty Boyd Dettre Library and Research Center. Papers, photographs, and art illustrate her boundary-pushing art and activism. An April 30 gallery talk will highlight the exhibition.

Notes:

1. Richard Meyer, “Hard Targets: Male Bodies, Feminist Art, and the Force of Censorship in the 1970s,” in WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007).