When first exhibited at the 2004 Whitney Biennial, 89 Seconds at Alcázar (2004) was a runaway success. Eve Sussman and the Rufus Corporation, a collaborative of actors, choreographers, technicians, and artisans of all kinds, created the enthralling video installation that was called “the only obvious smashing work on view.”¹ The 10-minute video is a reimagined, moving meditation on Las Meninas (ca. 1656), by Spanish court painter Diego Velázquez (1599–1660). It envisions the moments leading up to and following the painting’s iconic, transient scene.

Velázquez’s enigmatic painting has garnered a cult-fandom among the art-obsessed. The slice-of-life, monumental scene in Las Meninas offers a very modern viewpoint, similar to a photographic snapshot but created more than 200 years before the camera. Velázquez’s composition is clever, even revolutionary. The painting shifts the traditional viewing perspective to focus on the creator of the image rather than the image the creator is representing.

At the foreground of Las Meninas, Velázquez depicts himself before of a massive canvas with brush and palette in hand; next to him are members of the Royal Spanish court. However, the most prominent element for art historians is the indistinct mirror that can be seen at the very center background of the painting. Velázquez’s inclusion of the mirror, depicting a bust-length view of the King and Queen of Spain, allows the viewer to see beyond the canvas. His perspective suggests that the viewer is standing in the space occupied by the King and Queen. For the centuries of art leading up to this work, representational painting was rendered as though the surface of a canvas might be substituted for a window into another world, where the spectator looked in. Instead, Velázquez presents a painting that looks out at the viewing looking in. It is a complex, behind-the-scenes glimpse at the process of art-making itself.

So what can account for this drastic change in perspective?

At the same time Las Meninas was developed, the Arnolfini Portrait (1434), by Jan van Eyck, was hanging in the halls of the Spanish palace, or alcázar, that Velázquez walked every day. It is likely that Velázquez was very familiar with this work—as a result, many historians see Las Meninas as a direct reference to the mirror-motif originally used in Van Eyck’s work. The plot thickens, bringing us back to Sussman and the Rufus Corporation.

When Eve Sussman saw Velázquez’s Las Meninas at the Museo Nacional del Prado, she too was prompted to reimagine a painting that itself reimagined Van Eyck’s earlier work.

However, Sussman and the Rufus Corporation approached their journey into shifting spectatorship with a new medium and a new dynamic viewing perspective. And while the subject matter appropriates content from Velázquez’s work, Sussman describes 89 Seconds as “. . . about activating the viewpoint of the camera, so you see it’s not Las Meninas—it’s something different.”²

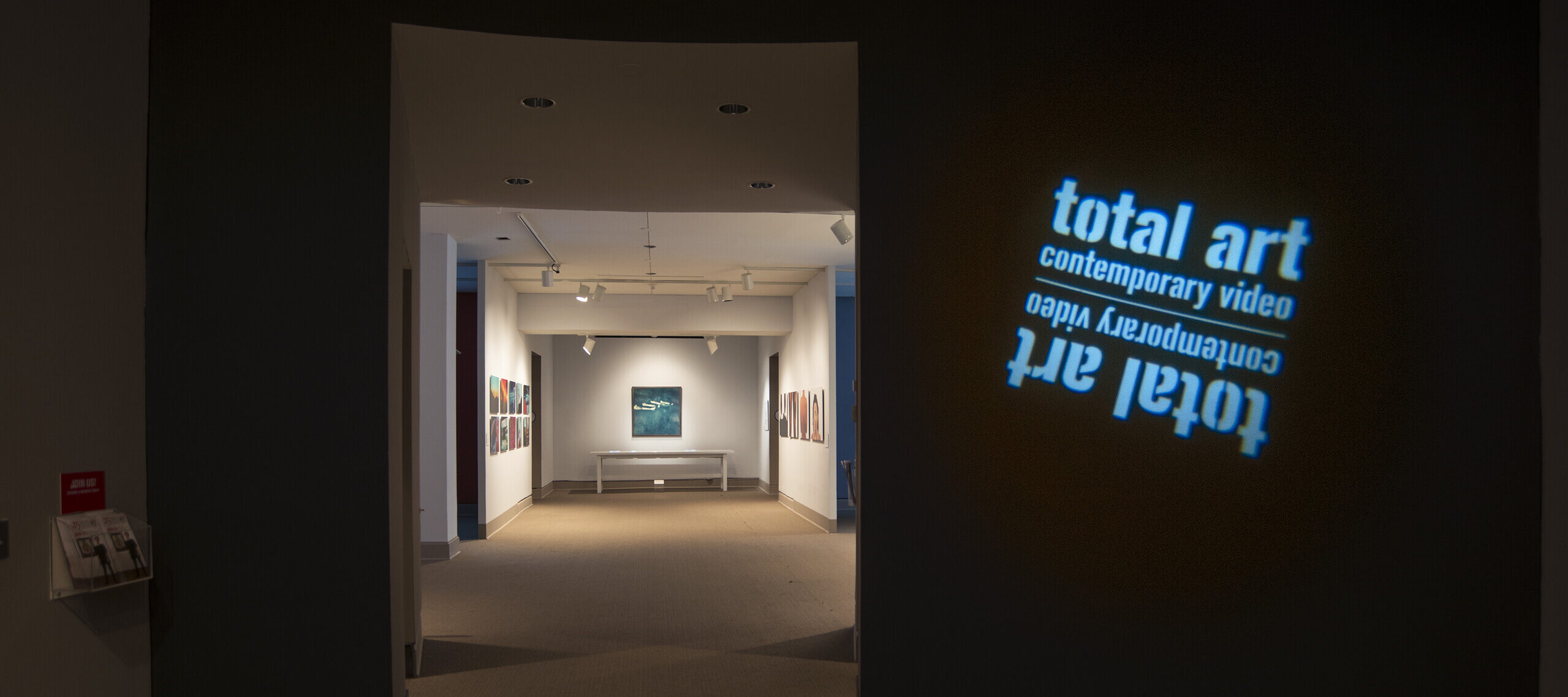

To learn more, visit NMWA on Wednesday, August 3, at noon for our weekly staff-led gallery talks. Associate Curator Virginia Treanor will facilitate a 30-minute conversation about 89 Seconds at Alcázar—join us during your lunch break, and return each Wednesday for up-close views of the other works in Total Art: Contemporary Video, on view at NMWA through October 12.

Notes:

1. Blake Gopnik, “Shifting Through the Whitney: Eve Sussman,” in the Washington Post, March 14, 2004. (http://www.rufuscorporation.com/wapost.jpg)

2. Eve Sussman as quoted in Carol Kino, “In the Studio: Eve Sussman,” in Art + Auction, July 2006. (http://www.rufuscorporation.com/anauc.html)