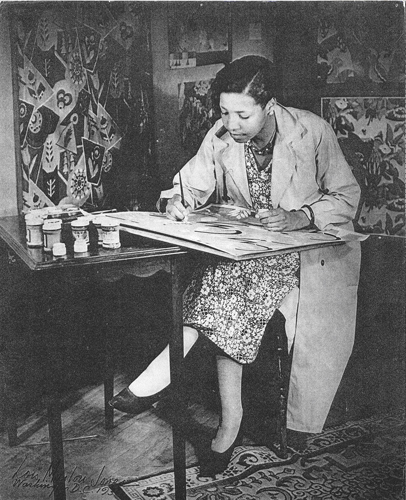

Loïs Mailou Jones’s long career had many chapters. One that is less-known is her career as a designer. In their 2000 study of women in design Pat Kirkham and Lynne Walker report that during the last century the involvement of women in this industry was not that unusual.1 However, aside from a few women involved in quilting in the 1920s and 1930s who rose above the relative anonymity of that activity, such as Wini Austin, Lucile Young, or Ruth Clement2, such opportunities were rare for an African American woman and probably were possible because of the relative anonymity with which designers worked and submitted designs. Jones would learn this was a double-edged sword.

In Boston, where Jones initially lived and worked, one of the institutions that provided design training was the Massachusetts Normal School of Art which was founded in 1873. Jones studied there between 1926 and 1927, and afterwards worked as a freelance textile designer for F.A. Foster Company in Boston and Schumacher Company in New York. What is evident in the corpus of Jones’s designs is her encyclopedic knowledge of art and design garnered through her dedication to her work experiences and studies. Her designs for cretonne fabric vary greatly, from more traditional floral and leaf designs to

Design for Cretonne Drapery Fabric (Palm Trees: oranges, yellows, green), c. 1928, which presents a Caribbean-esque, if not African-esque, whimsy. Another design shows a seated statue that evokes African art, whose torso is festooned with a diamond “dazzler” pattern that recalls Navajo weaving conventions of the 1880s and 1890s. This demonstrates how references to a multiplicity of cultures and media phenomena seemed to flow effortlessly and copiously from the well of Jones’s creative impulses.

By the early 1930s Jones was segueing into the next episode of her career, and eventually gave up design work to pursue “fine” art: namely, painting. At this time she joined the faculty of Howard University initially as an instructor in design and later in watercolor. As Tritobia Hayes Benjamin records, Jones was increasingly perturbed that despite the prizes and citations that her designs garnered for her, she remained an anonymous entity in the design world. Jones’s design work was completely different from her paintings, as she worked to differentiate the two to signal her new vocational aspirations.

Jones’s struggle with her role in art and design has particular resonance in the context of the larger American art scene between the two World Wars. It highlights not only issues around authorship which surrounded the creativity of designers as well as craftspersons and women, but also questions the role of art in society.

Jones’s sense of design, however, seems not to have deserted her. It resurfaced with her experiences in Haiti starting in the 1950s and her travels to Africa in the late 1960s and early 1970s, which brought out a more overt cultivation of pattern and form in a non-narrative format. It might be said that in these paintings Jones came full circle back to her original love of design, after having gained the recognition that eluded her early on. In the end, Loïs Mailou Jones left a rich corpus of paintings that show the restlessness of her creative expression, ability, and willingness to respond to all that life offered her.

Adapted from “Loïs Mailou Jones: From Designer to Artist,” from Loïs Mailou Jones: A Life in Vibrant Color (The Mint Museum, Charlotte, North Carolina, 2009)

Notes

1. Pat Kirkham, and Lynne Walker, eds. Women Designers in the USA, 1900–2000: Diversity and Difference, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, published for the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, New York, 2000).

2. Pat Kirkham and Shauna Stallworth, “Three Strikes Against Me: African American Women Designers” in Ibid, p. 132–134.