Women played a vital role in shaping the visual culture of the Low Countries, present-day Belgium and the Netherlands, during the 17th and early 18th centuries. Women Artists from Antwerp to Amsterdam, 1600–1750 is the first-ever survey exhibition of women artists from this region and time period. Including more than 40 artists, with many works on view in the United States for the first time, it demonstrates that women were an active and consequential part of one of the most robust and dynamic artistic economies of the era.

Presence

Portraits of women artists, their signatures, and existing works in a wide range of mediums and genres attest to their presence during the 17th and early 18th centuries. Whether they depicted themselves with the tools of their trade or conspicuously and proudly placed their signatures on their work, women were not hesitant to declare their roles as creators. Portraits of them by others indicate the respect and renown they enjoyed in society. Some were immortalized in paint by peers or family members, and others enshrined within the pages of published biographies, which ostensibly ensured their legacies far and wide.

Judith Leyster (1609-1660) and Maria Schalcken (ca. 1645/50-ca. 1700) both depicted themselves at work in front of their easels, their hands holding paintbrushes and palettes. Neither is dressed in clothing appropriate for the messy work of painting; rather, they present themselves as well-dressed women with wealth and social standing. This type of self-presentation hews to a tradition begun in the Italian Renaissance, as artists sought to distance themselves from the overtones of manual labor that was associated with painting in earlier eras. Maria van Oosterwijck (1630-1693) was a highly admired and successful still-life artist whose likeness was captured in a portrait by Wallerant Vaillant (1623-1677). Like Leyster and Schalcken, she is clearly identified as a painter.

Many women artists asserted their authorship through signatures or initials. Maria Faydherbe (1587-after 1633) carved the Latin words “MARIA FAYDHERBE ME FECIT” on the base of her sculpture Virgin and Child (ca. 1632). Translated as “Maria Faydherbe made me,” this signature is remarkable not just for its unapologetic declaration of authorship, but also because it was rare for any sculptor in the city of Mechelen at the time to sign their work. The unknown maker of an embroidered darning sampler (1761) proudly stitched her initials, “GM,” into the work itself. The border, embellished with an embroidered vine of flowers, is typical of the decoration found on high-quality clothing of the period. This type of delicate textile only rarely survives; its maker and her family likely took great pride and care in its preservation.

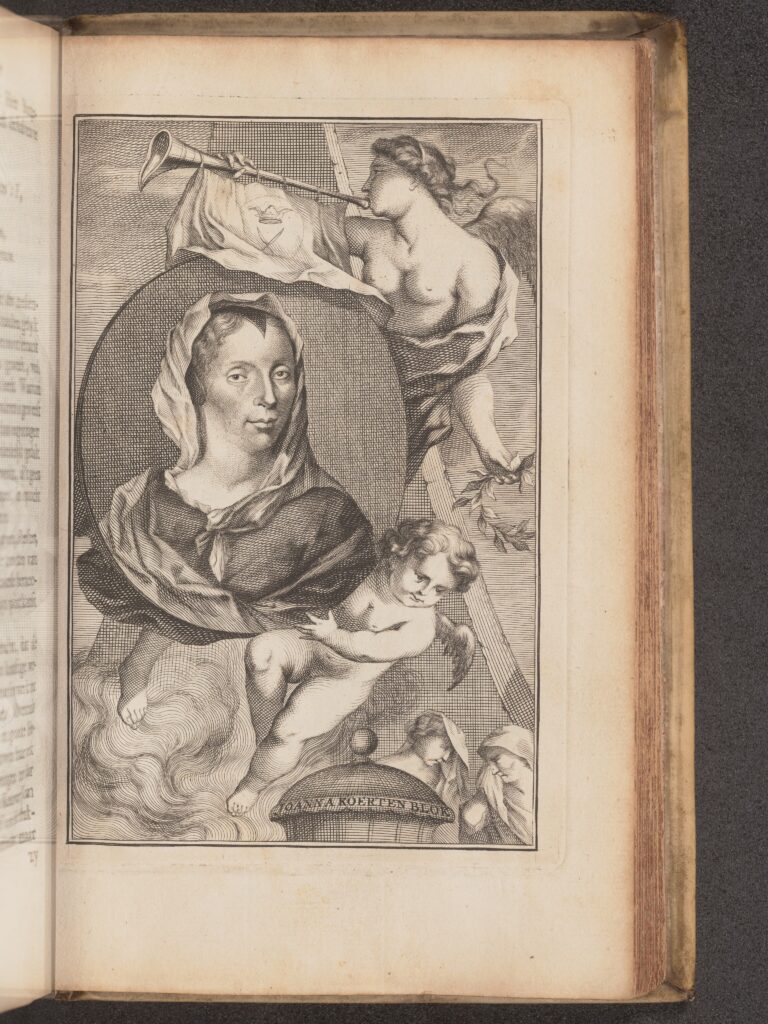

Other women were written about in published and widely read sources. For instance, Arnold Houbraken’s De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schil-deressen (The Great Theatre of Dutch Painters and Paintresses) (first edition, 1715) records the names of women working in a variety of artistic fields. This multivolume tome was also illustrated with artists’ portraits, including those of Anna Maria van Schurman (1607-1678), Johanna Koerten (1650-1715), and Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717).

Testament

In an essay for the exhibition’s catalogue, co-curator Virginia Treanor writes that examples such as the works above “…reveal that far from being dismissed, overlooked, [or] working in obscurity during their lifetimes, many women were acknowledged for their talents and contributions. [They] consistently appear in records throughout the period, attesting to their undeniable presence.”

Want to learn more? Visit Women Artists from Antwerp to Amsterdam, 1600-1750, through January 11, 2026, and buy the exhibition catalogue from NMWA’s museum shop.