Contemporary large-scale paintings and sculptural hybrids are on view in NO MAN’S LAND: Women Artists from the Rubell Family Collection. The exhibition imagines a visual conversation between 37 women artists from 15 countries exploring images of the female body and the physical process of making.

Josephine Meckseper, Wangechi Mutu, Solange Pessoa, and Marlene Dumas integrate fragmented and constructed bodily forms in their works.

What’s On View?

Josephine Meckseper’s American Leg, 2010

“I see my work as a call for street activism,” says Josephine Meckseper (b. 1964, Lilienthal, Germany). “My aim is to present consumer display systems that have an auto-critique built within.” In her series of sculptures formed from consumer products, Meckseper reflects on the subversive power behind commercialism.

With its mirrored base, American Leg evokes the glamorous presentation of banal objects in retail spaces—while reflecting the legs of visitors standing nearby. This sculpture’s glass vitrine references store-front displays that are often smashed during periods of civil unrest.

Wangechi Mutu’s The Evolution of Mud Mama from Beginning to Start, 2008

Wangechi Mutu (b. 1972, Nairobi) blends watercolor with collaged photo clippings and gold leaf to build biomorphic forms that sometimes merge into female figures. Mutu’s work often celebrates the female body. She says, “Females carry the marks, language, and nuances of their culture more than the male. Anything that is desired or despised is always placed on the female body.” Her constructed bodies often incorporate images that mark war and injury, but the collaged elements in The Evolution of Mud Mama from Beginning to Start depict the natural world, alluding to the Garden of Eden or a mythical, primordial time.

Solange Pessoa’s Hammock, 1999–2003

In her large-scale sculptures, Solange Pessoa (b. 1961, Ferros, Brazil) combines elemental materials and abstract shapes to develop a range of organic associations and psychological moods.

In Hammock, fabric pouches resemble proliferating biological growths. By suspending the sculpture from two points, Pessoa emphasizes the weight of the pouches’ contents, whether a biological substance or cultural history and meaning. She notes that “physicality,” which she achieves though scale, density, and abundance, is essential to her art.

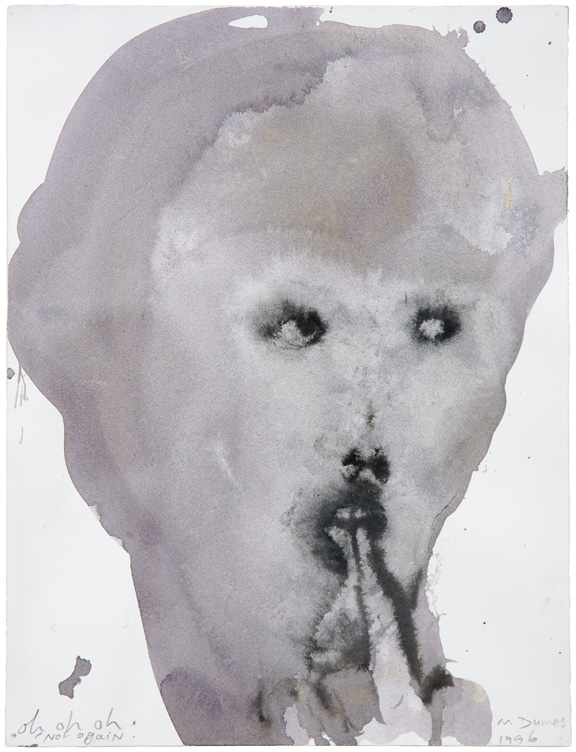

Marlene Dumas’s Oh, Oh, Oh, Not Again, 1996

Marlene Dumas (b. 1953, Cape Town, South Africa) frequently finds inspiration in newspaper and magazine photos. “Yes, I paint portraits and I use the human figure, but actually I want to paint what you cannot see,” says Dumas. “More the spirit of things, or the relationships and the dialogue between them.”

Dumas’s figure in Oh, Oh, Oh, Not Again is arranged for maximum drama against an empty background. In a subdued and eerie palette, the image on the paper seems to appear out of almost nothing. Ink and metallic acrylic bleed together to form a haunting expression.

Visit the museum and explore NO MAN’S LAND, on view through January 8, 2017.