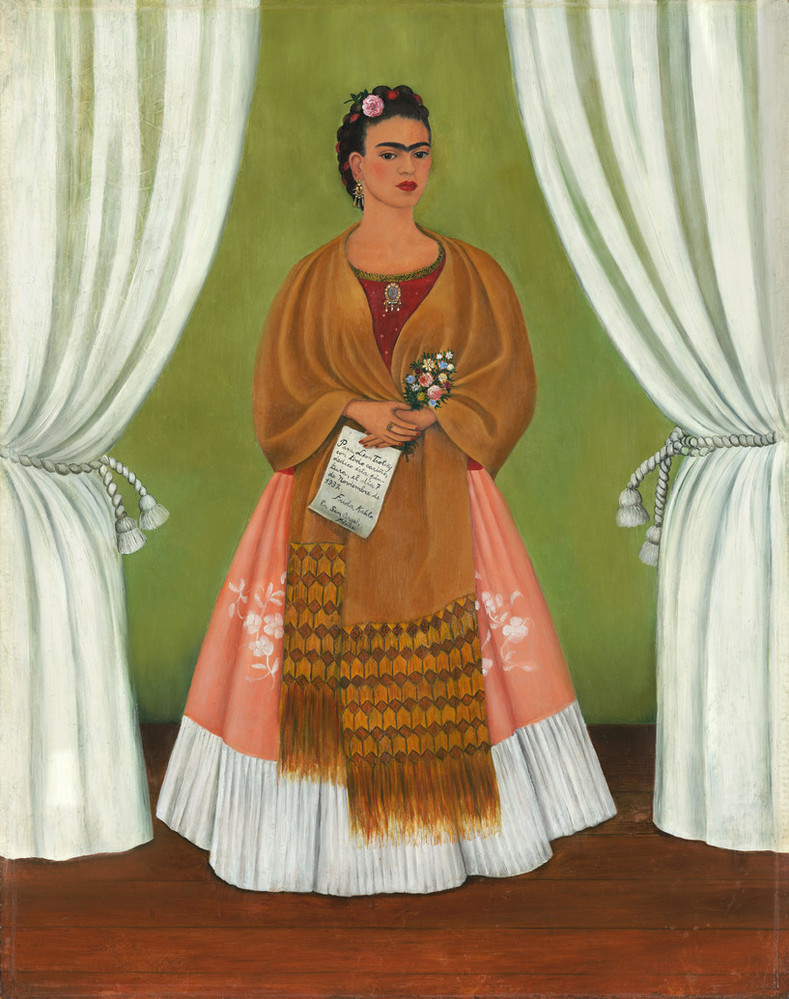

We are fortunate to have an important Frida Kahlo (b. 1907) painting in our collection, Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky (1937). It is the only Kahlo in a public collection in Washington, D.C. One of the most fascinating artists of the 20th century, Kahlo created intense and revealing self-portraits that chronicle her challenging relationship with her husband Diego Rivera, leader of the Mexican Muralists; her struggles with her broken body; her identity as a bisexual person; her devotion to Mexicanidad; and her involvement with the worldwide Communist Revolution.

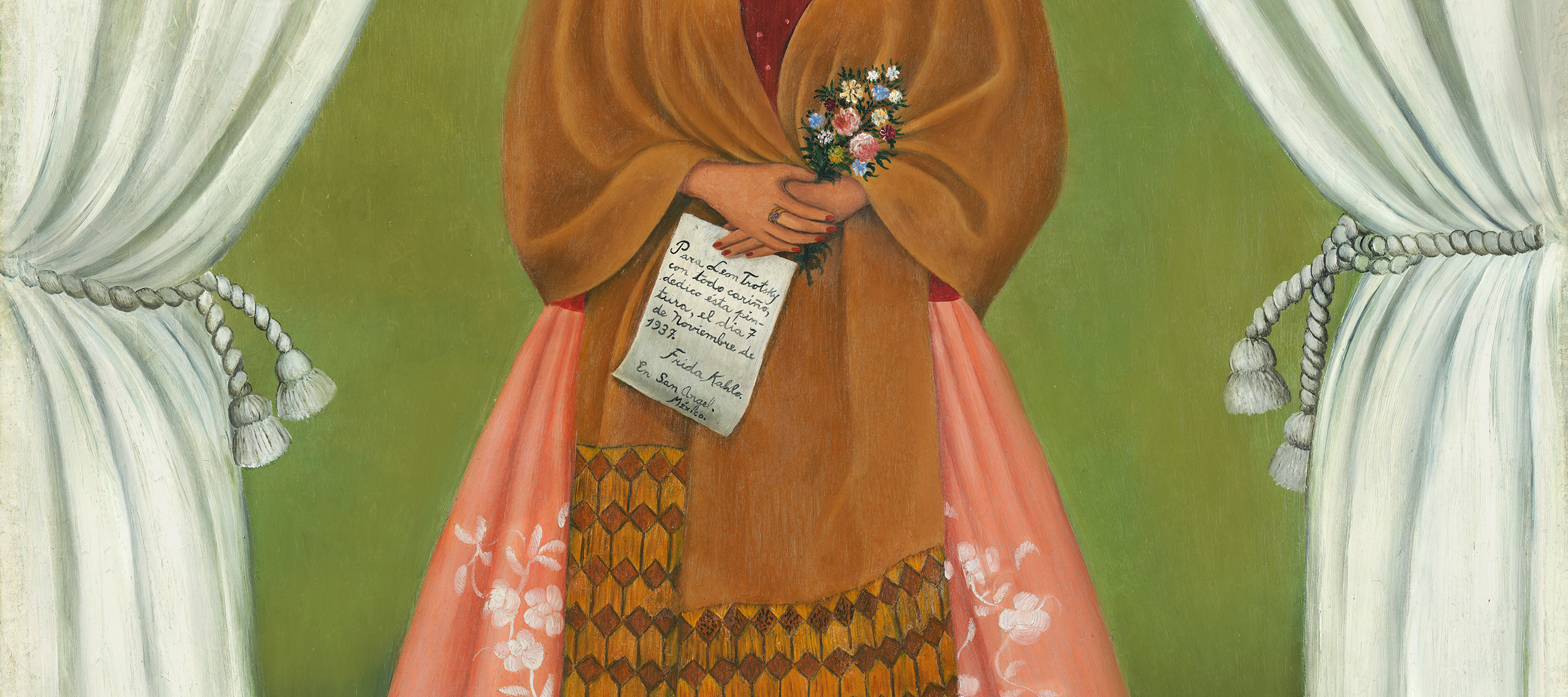

In Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky, Kahlo is framed between two curtains—a new Madonna of the people—wearing traditional Tehuana attire. She holds a letter that is both a declaration of political allegiance and personal affection for the exiled Russian Communist leader Leon Trotsky, with whom she had developed a close friendship and had a brief affair. You can explore the painting in detail on Google Arts & Culture.

Upon arriving in Mexico in January 1937, and under Rivera’s protection, Trotsky and his wife Natalia Sedova lived in Casa Azul, Frida’s family home, for two years. Frida enshrined their relationship in this portrait, which she gave to Trotsky on his 60th birthday. It hung in his private study in Casa Azul until the Trotskys moved to a new safe house in 1939.

While much has been written about Kahlo since the groundbreaking 1983 biography by art historian Hayden Herrera, my favorite book featuring the artist—Barbara Kingsolver’s novel The Lacuna (2009)—covers this particular period. My favorite chapters follow the book’s protagonist as he begins working for Rivera as a mural plasterer; becomes the family cook, friend, and confidant to Kahlo; and serves as Trotsky’s personal secretary just prior to his assassination. It is thrilling to me that NMWA’s painting figures into the story.

As Kingsolver said, “I didn’t initially plan to write about Kahlo….But she grew on me. I read all the biographies, then went to Mexico City to see artworks, archives, and the Rivera and Trotsky homes….Frida was everywhere: her doodles even cover the margins of Diego’s financial ledgers. I felt her poking at my shoulder, saying, ‘Muchacha, you’re ignoring me.’ I began to understand her not as a martyred icon but as a roguish, complicated person. She was a natural for drawing out my reclusive protagonist, they had excellent chemistry.”

At NMWA, you can explore primary source material on Kahlo in the Nix-Huber archive, which includes letters between Kahlo and her mother, exchanged during Kahlo’s travels in the United States in the 1930s. These letters are quoted extensively in Celia Stahr’s new book, Frida in America: The Creative Awakening of a Great Artist (2020). Now that I have a bit more time to read about Kahlo, it’s on my list. I hope that you and yours stay well and find new ways to immerse yourself in the stories of great women artists.