As I filled out my mail-in ballot recently, I thought about ways that paper has changed history. Beginning in 800 C.E., mass production of paper enabled the spread of information, literacy, and action across the globe, including the ideals of a fledging new republic in 18th-century America. This ubiquitous material is a vessel for our values, history, hopes, and obligations to one another as human beings. In our newest exhibition Paper Routes—Women to Watch 2020, now on view at NMWA, many of the featured artists explore paper’s long association with identity and advocacy, using their practices to explore social or political issues.

In Black Power Wave: Drawing For Protest (2017) Oasa DuVerney (whose work is sponsored by our committee in New York, b. 1979) reminds us of the power of art to incite overdue conversations on race. DuVerney’s piece features protest placards that, when assembled together, depict a large cresting wave drawn in graphite. As the artist says, “This drawing is prepared for political action, evoking pride in Black power.”

I’m also moved by the intersection of the personal and the political in work by Nigerian-born Mary Evans (United Kingdom, b. 1963). She describes the silhouetted figures in her large-scale scenes as “approximations of African people” and through them, she responds to the way Black bodies have been, and continue to be, violated. As she writes in her statement for the exhibition catalogue, she is interested in paper’s “durability and delicacy, which is reminiscent of the tenacity and vulnerability of all people, but in particular of African peoples and all that they have endured.” Here, her brown Kraft paper figures are haunting and ephemeral, like shadows passing by.

Annie Lopez (Arizona, b. 1958) also connects art to her cultural history, printing vivid blue cyanotype images and texts on tamale wrappers, from which she makes meticulously sewn garments. The artist says, “I have always been the family historian, and the garments I create contain stories that address childhood, relationships, family, stereotypes, racism, and tragedy. The dresses take my place in telling these stories—they surround me and protect me, like armor.” Recording history on paper is commonplace; Lopez’s wearable paper sculptures show us how we are always cloaked in our families’ stories.

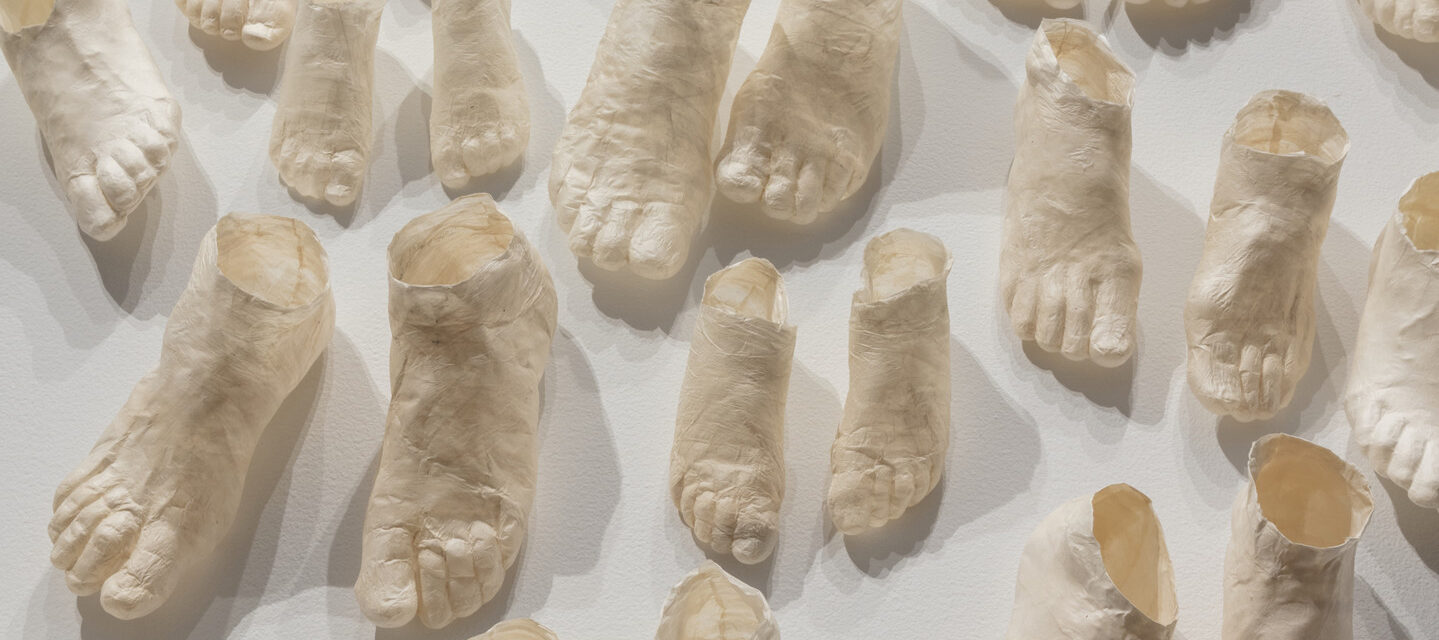

In Tide (2019), Hyeyoung Shin (Greater Kansas City, b. 1973) uses Jiho-gibeop, a traditional Korean method of paper casting from objects. Inspired by the worldwide Women’s March rallies in 2017, Shin casts individuals’ feet to portray the paths that people take based on their beliefs. She writes in the catalogue that she sees paper “as an embodiment of culture that has the ability to hold and connect experiences and memories.” Throughout this exhibition, I am struck by how paper can be so versatile, connecting us to moments that remind us, ideas that inspire us, and causes that move us to act for the greater good.