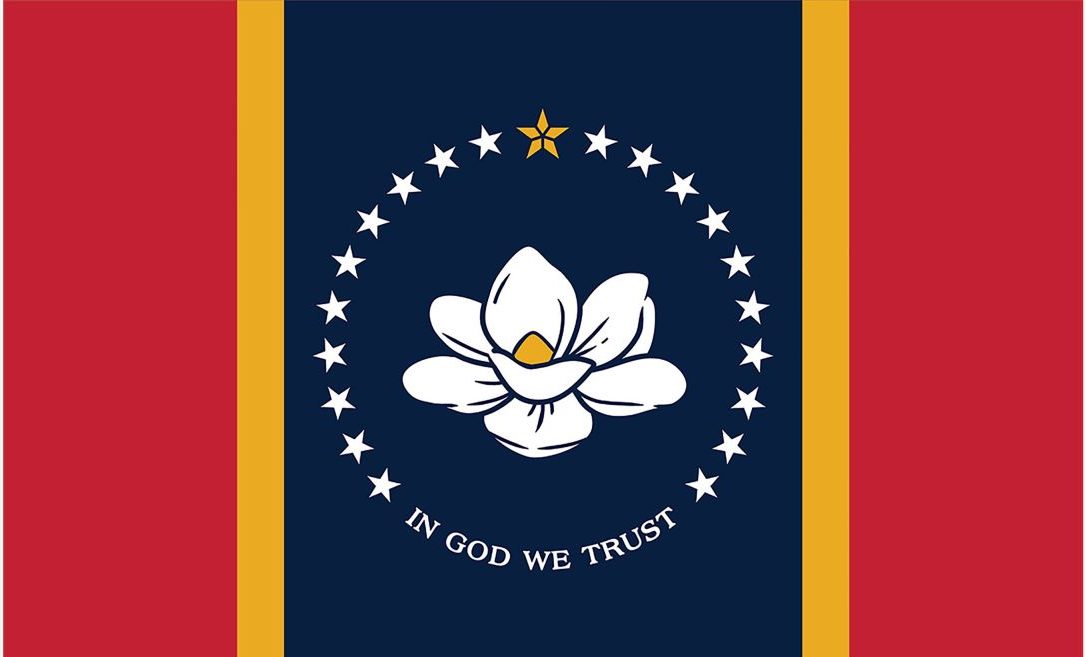

Web designer Sue Anna Joe, a native of Mississippi, created the central magnolia motif on Mississippi’s new state flag, which replaced the original design’s Confederate battle emblem at the beginning of 2021. On the occasion of the NMWA exhibition Sonya Clark: Tatter, Bristle, and Mend, we asked Joe to consider Clark’s own Confederate battle flag and truce flag works, which also deconstruct “…the symbol, the history, and the hatred,” as Clark describes.

I recently explored Sonya Clark: Tatter, Bristle, and Mend at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Two of her pieces, Monumental Cloth (Sutured) (2017) and Unraveling (2015), struck me at the heart. These works illuminate the dialogue on race relations in our country, proposing a deep reflection on our potential as a society and the work required to fulfill it. Last year I contributed to Mississippi’s new state flag design, which replaced its previous Confederate-themed counterpart. My creative process mirrored the propositions in Ms. Clark’s work; I held my own personal conversations about Mississippi’s future in light of its past, asking how those of us who call the state home can forge a collective path toward healing.

I embarked on the flag selection process by submitting my own work to the open call for designs. I launched my creative process from plain paper akin in function and appearance to the fabric Ms. Clark used to recreate the American Civil War truce flag in Monumental Cloth (Sutured). Her piece asks us to reimagine a society born of this dishrag, a symbol of peace and unity, rather than the Confederate battle flag. Much like the truce flag, my humble and utilitarian drawing paper served as a blank canvas for fashioning a banner for a united Mississippi.

After considering other symbols, I drew a southern magnolia bloom as my central element. To me, it prevails as the symbol most worthy of Mississippians; it’s recognizable, relevant, and representational. It links us together. In a similar spirit, the truce flag appeals to uniting divisions through common ground. The truce flag is virtually unknown for its role in the Civil War, and while Mississippians recognize the magnolia, its ubiquity and history as an official state symbol are often taken for granted. Notwithstanding, both symbols demonstrate within their own contexts that we don’t need to dig deeply to discover symbolic ties with our neighbors.

Completing my creative journey required meticulous effort: exploring concepts, iterating on variations, and fine-tuning details. Ms. Clark’s Unraveling illustrates the same process, in which mindfulness, dedication, and persistence are essential in dismantling systemic racism, and the effort of a few is not enough. By inviting the public to literally unravel the Confederate flag, her piece reveals how mass participation is critical for progress toward racial harmony.

Many people contributed to the removal and replacement of Mississippi’s old flag: legislators, the flag commissioners, nearly 3,000 designers, and the voters. The first threads pulled apart in tight-knit racist institutions often resist the strongest, but we loosened them with the adoption of a new flag. We hope the fabric will now give way to the repurposing of common threads, weaving a new story for Mississippians.