Renowned for her intricate wood engravings of urban cityscapes and rural countrysides, American printmaker Grace Arnold Albee (1890–1985) explored the dualities of the natural and built worlds. During her career, which spanned more than 60 years and several cities, she produced about 250 prints, marking her as one of the most important American Regionalists. Many of her preparatory drawings and prints—wood engravings, linocuts, and more—are part of NMWA’s collection.

Along with her husband, artist Percy F. Albee, and the couple’s five boys, Albee lived in Providence; Paris; New York City; Bucks County, Pennsylvania; suburban New York; and rural Rhode Island for years at a time. Albee maneuvered between homemaking and art making, incorporating each new environment into her prints.

Process and Preparation

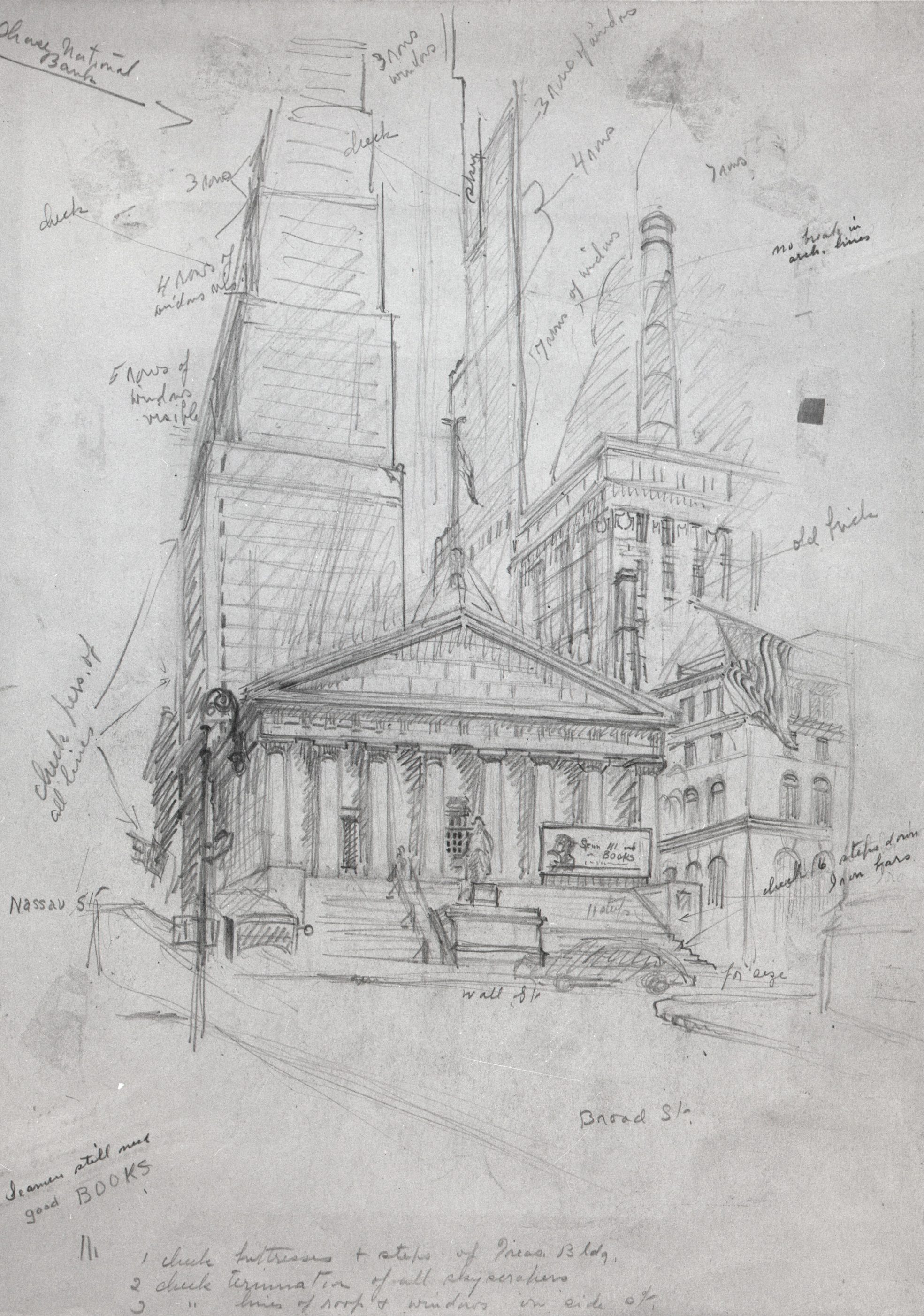

Albee’s 1947 study of Manhattan’s Sub-Treasury building illuminates the artist’s process and captures the energy of the city. Skyscrapers erupt behind the Greek Revival building, cars and pedestrians dot the street, and flags adorn the skyline. The artist sketched this subject on site, indicating its general forms, shading, and jotting down notes, an essential first step in her method. As with her other wood engravings, Albee would have then taped the drawing to a piece of Chinese boxwood, traced its outlines onto the block, cut away the pieces she wished to leave white, and applied ink to the remaining sections.

Capturing Time

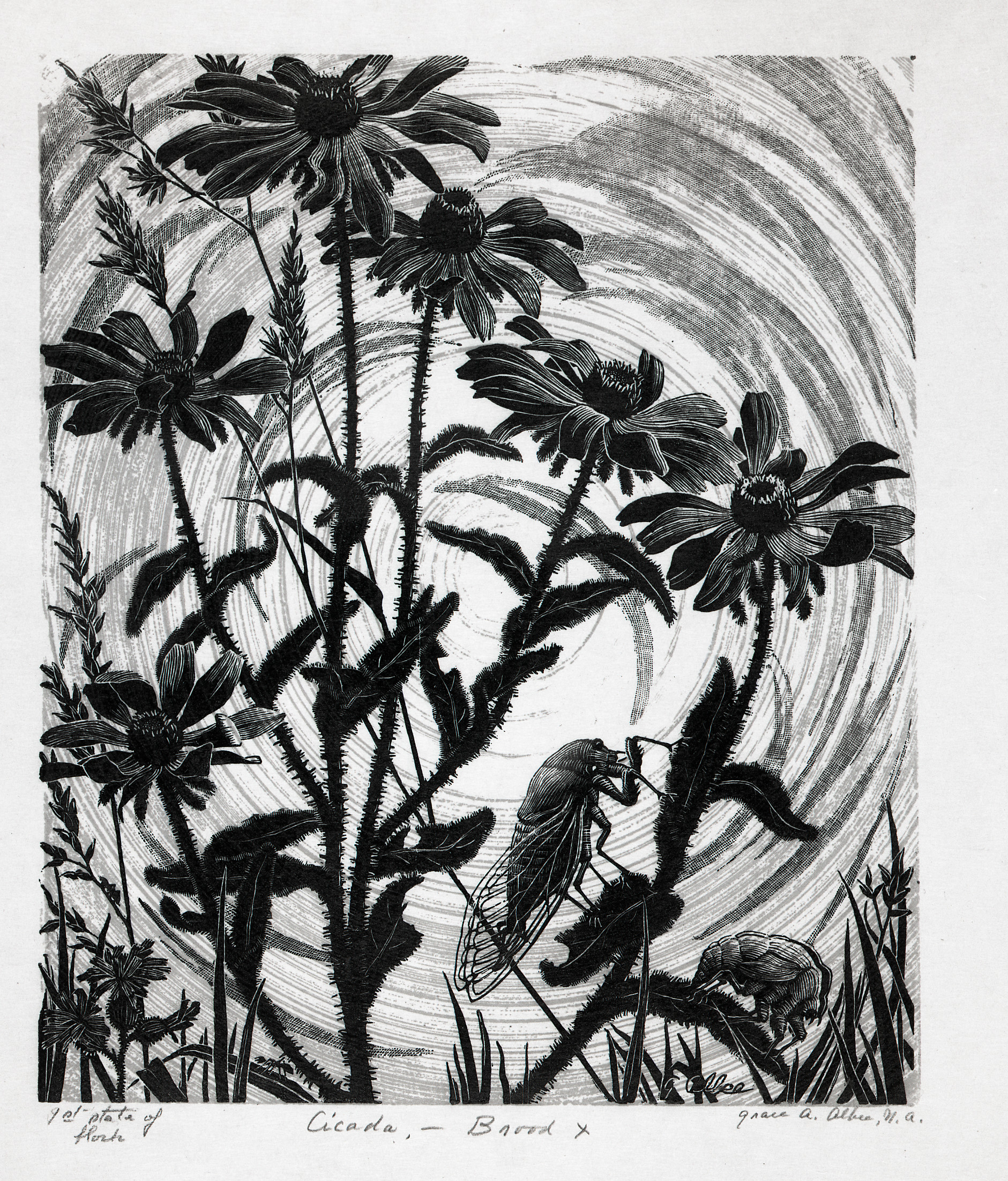

Albee’s Cicada—Brood X (1970) demonstrates her artistic capabilities. The print documents a pair of cicadas perched on the stems of wildflowers. Each blade of grass is delicately rendered; the hairy flower stems, imperfect petals, and lacy cicada wings appear almost tactile; and the low sun beams in ethereal spirals. The print encapsulates the sights of summer and signifies one of Albee’s favorite themes: the passage of time. Since the eastern U.S. just experienced the most recent appearance of Brood X cicadas, many are aware that these creatures live below ground for 17 years and spend only a brief, noisy time above ground to mate before dying off.

Made With Love

Albee’s legacy was fondly remembered by her son Percy Frederick Albee Jr., who went by P. Frederick Albee, during a retrospective of his mother’s work at NMWA in 1999. Albee Jr. recalled that his mother observed and engraved the world with love. Alongside her well-known landscapes, she also made prints depicting her husband and children, a funeral for a family pet, and even an elaborate prank she played on a family friend.

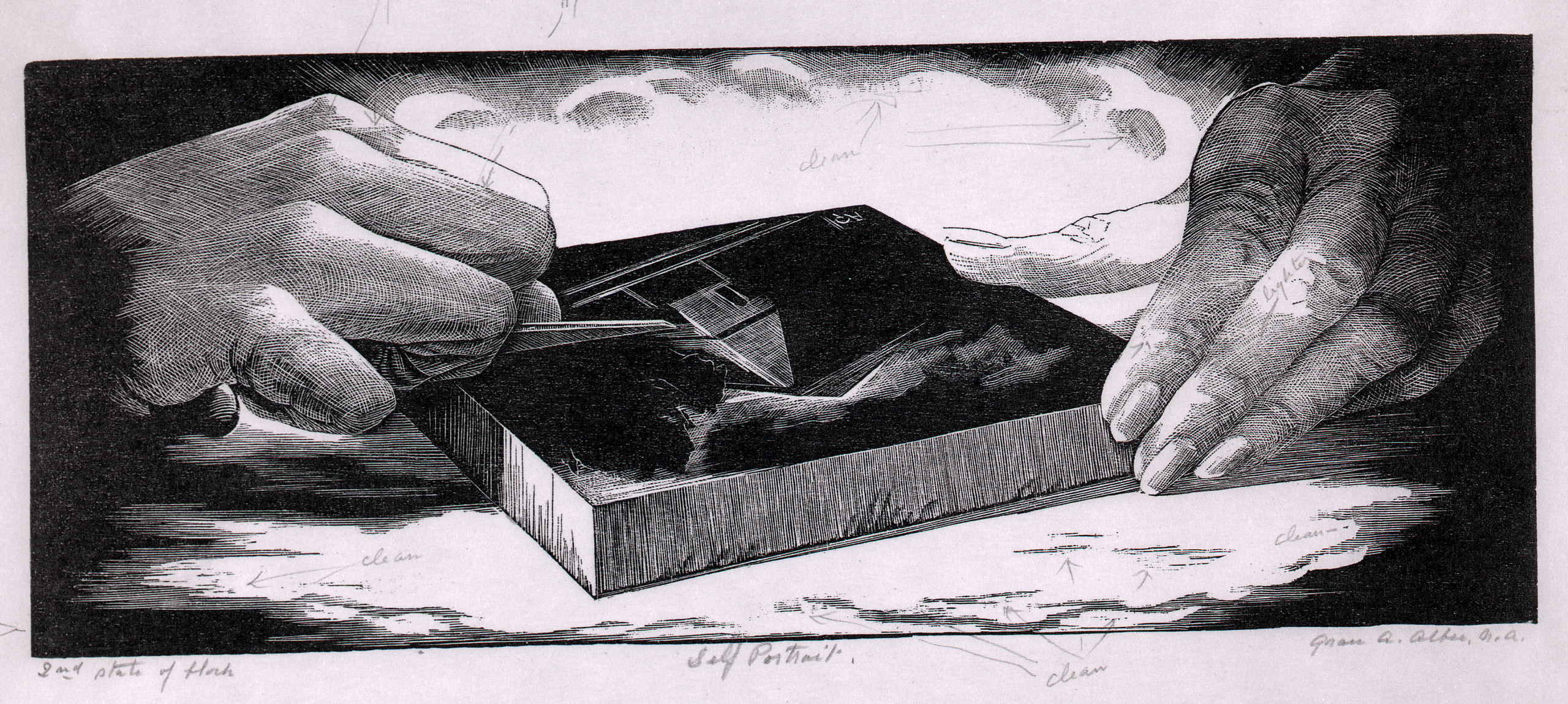

For all of her engravings, Albee only ever executed one self-portrait. Completed in 1966, Self-Portrait shows the artist’s hands as she engraves a woodblock, her face out of view. As Albee Jr. described, “She is saying to her viewers, ‘If you want to know me, don’t look at my face, look at my hands. They are the instruments of my character.’”