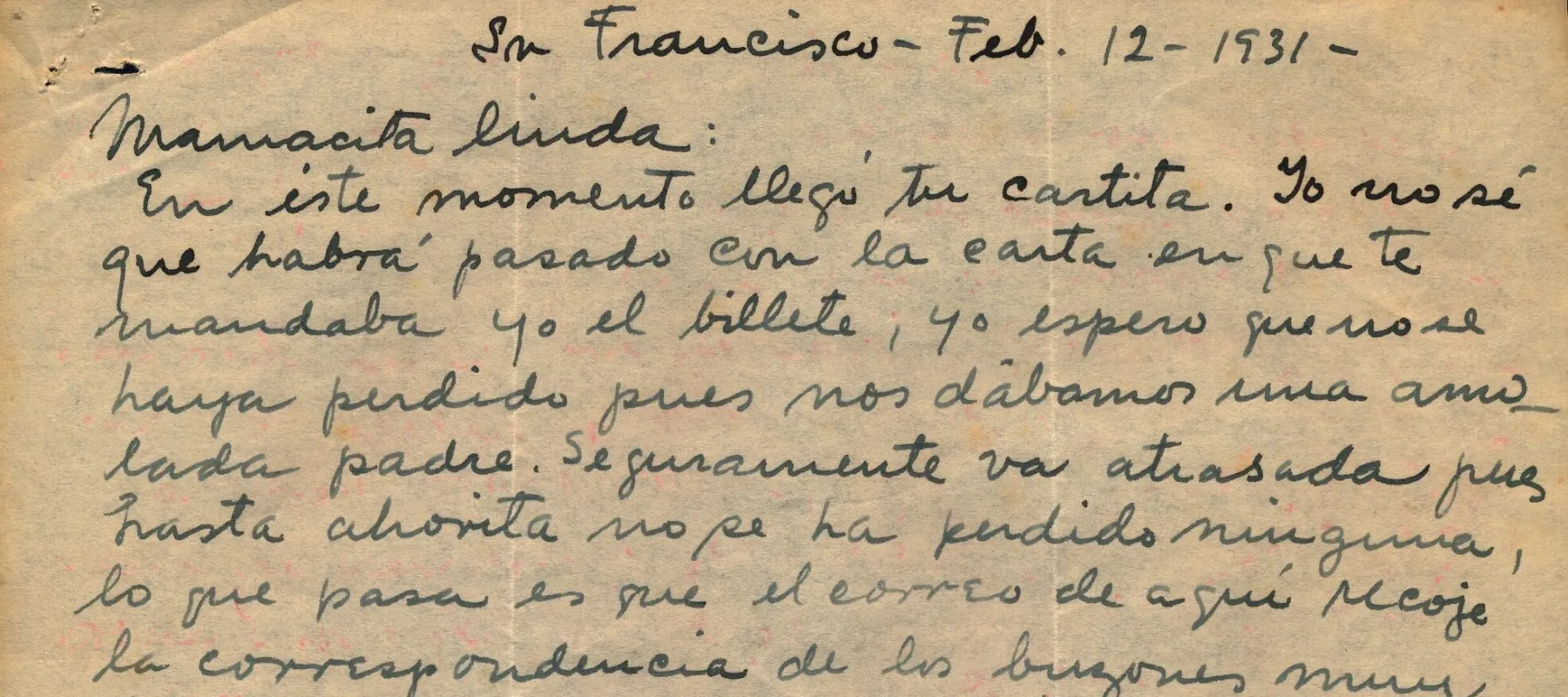

Today, on her 105th birthday, we celebrate Frida Kahlo, whose 143 finished paintings focused on Mexican culture, gender identity, social justice, and often pain. Born on July 6, 1907, to Guillermo Kahlo and Matilde Calderón de Kahlo, the artist, a vibrant personality and talent, lived and died in her famed “Blue House” in Coyoacán, Mexico. For much of her life, she was restricted physically, following a bus accident that occurred when she was a teenager. At NMWA, through July 31, the exhibition Mamacita Linda: Letters between Frida Kahlo and her Mother showcases the artist’s family correspondence. In comparison to the intensity of many of her paintings, the letters in Mamacita Linda show a humorous, loving side of the young Kahlo.

Critics have claimed that Kahlo and her mother had a strained relationship, perhaps as a result of Calderón’s disapproval of Kahlo’s marriage to muralist Diego Rivera or Frida Kahlo’s feelings about her parents’ own marriage. However, if animosity existed, it is not reflected in Kahlo’s warm and open letters, which are part of The Nalleke Nix and Marianna Huber Collection: The Frida Kahlo Papers. During the beginning years of the 1930s, the mother-daughter pair shared a close bond (Calderón de Kahlo died of breast cancer in 1932). Many of Frida Kahlo’s letters to her mother are addressed to “Mamacita Linda,” which translates to “pretty mama.” Her letters close affectionately, too: “Whatever I can send you, I’ll send you,” “And for you, all my love,” and “Don’t forget about your Frieducha who loves you.”¹

Their expressions of adoration may have been heightened by Kahlo’s youth and inexperience. She was in her twenties, but this period includes a time when Kahlo had just moved to America with Rivera, who was having significant professional success. She was experiencing culture shock and relapses of pain, and she knew that her mother was also in poor health.

Frida Kahlo’s complexity was later reflected in the bold colors and symbolic imagery on her canvases. As Kahlo described her work, “Really I do not know whether my paintings are surrealist or not, but I do know that they are the frankest expression of myself. Since my subjects have always been my sensations, my states of mind, and the profound reactions that life has been producing in me, I have frequently objectified all this in figures of myself, which were the most sincere and real thing that I could do in order to express what I felt inside and outside of myself.”² The contradictions in her life and work, the dichotomy between the woman who painted her dark and unjust view of nature as well as “Frieducha,” the girl who sent jokes to her mother in the mail, continue to command viewers’ attention. Now, at 105 years old, she still represents defying limitations.

Notes:

1. The quotes included here were taken from NMWA’s Mamacita Linda: Letters between Frida Kahlo and her Mother, from the Nelleke Nix and Marianne Huber Collection: The Frida Kahlo Papers .

2. The quote included here was taken from “The Life and Times of Frida Kahlo,” a film by Amy Stechler on PBS (2007).