During the fiscal year that ended in June 2021, major acquisitions embodied NMWA’s mission to celebrate diverse women artists. New works include prints by Emma Amos and Helen Hardin; photographs by Yevonde and Dianne Smith; and large-scale sculptures by Deborah Butterfield and Berlinde de Bruyckere. The museum was also able to acquire works by artists featured in recent exhibitions, including Delita Martin, Mary Ellen Mark, and Judy Chicago. Although NMWA’s building is currently under renovation, the collection’s recent growth sparks energy and inspiration as the museum plans for the future.

Emma Amos (1937–2020)

Amos interrogated the art-historical status quo through an inventive approach to color and form in her figurative and abstract paintings, prints, and textiles. Influenced by Western European art, Abstract Expressionism, and the civil rights and feminist movements, Amos probed issues of racism, sexism, and ethnocentrism in her art. In 1963, she became the sole female member of Spiral, a fleeting but significant collective of African American artists in New York City who explored the role of Blackness in art.

Pool Lady (1980) is Amos’s contemporary take on the bather subject commonly found in art history. She features a Black woman—likely a self-portrait—rarely seen in portrayals of “bathers” in Western art. This confident figure confronts the viewer with a direct gaze and defies stereotypes associated with Black femininity.

Deborah Butterfield (b. 1949)

Butterfield is renowned for the sculptures of horses that she has been creating for more than 40 years. A skilled equestrian, the artist has centered her practice on sculptures that—while semi-abstract—demonstrate her expert knowledge of equine anatomy and evoke the animals’ spirits. Butterfield has said, “I wanted to do these big, beautiful mares that were as strong and imposing as stallions but capable of creation and nourishing life. It was a very personal feminist statement.”

More than seven feet high and nine feet long, Big Horn (2006) is named after an area in Bozeman, Montana, near Butterfield’s home. As is characteristic of her style, the sculpture involved a labor-intensive process of casting bronze from wooden branches, which she then assembled and welded into the shape of a horse, evoking movement, shape, and color. Each work, including Big Horn, is a one-of-a-kind cast sculpture.

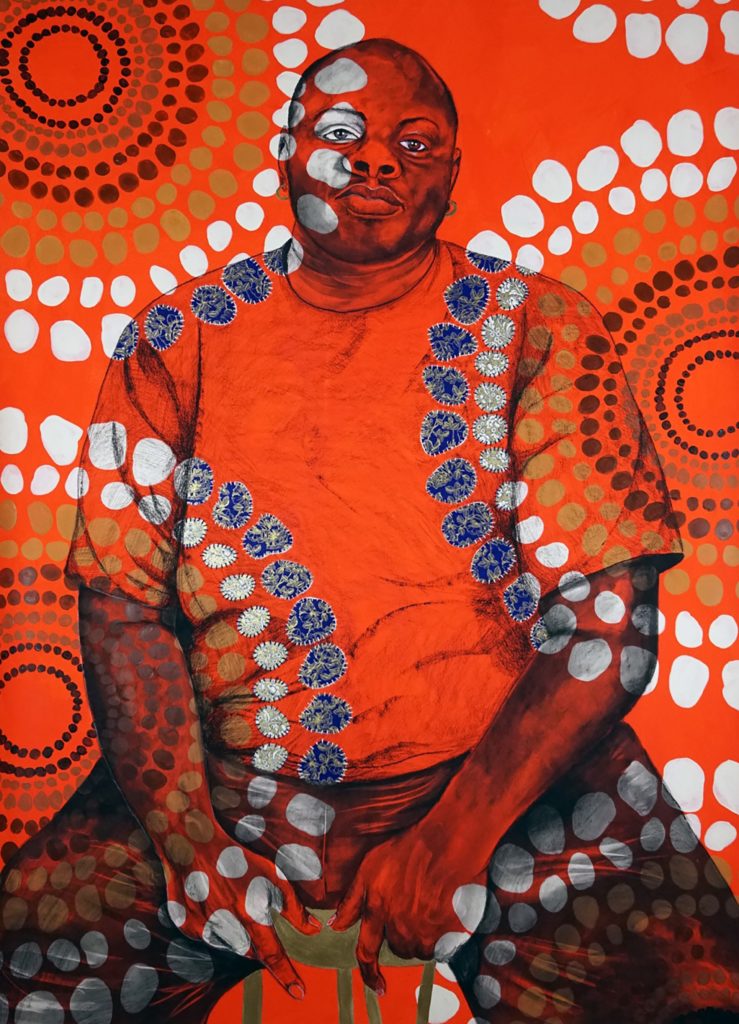

Delita Martin (b. 1972)

Martin creates large-scale prints onto which she draws, sews, collages, and paints. She claims space for her subjects, creating a powerful presence that highlights the historical absence of Black bodies in Western art. A recurring theme throughout Martin’s work is the connection between past and present generations, which she locates in a transitional space between the physical and spiritual worlds. She conveys these connections through symbols such as circles, birds, and masks of West Africa.

The museum acquired Believing in Kings (2018), which was featured in the 2020 exhibition Delita Martin: Calling Down the Spirits. This work prominently features circles, which appear in pattern elements as well as hoop earrings—they are symbolic in Martin’s work of the moon, infinity, wholeness, and cyclic movement.