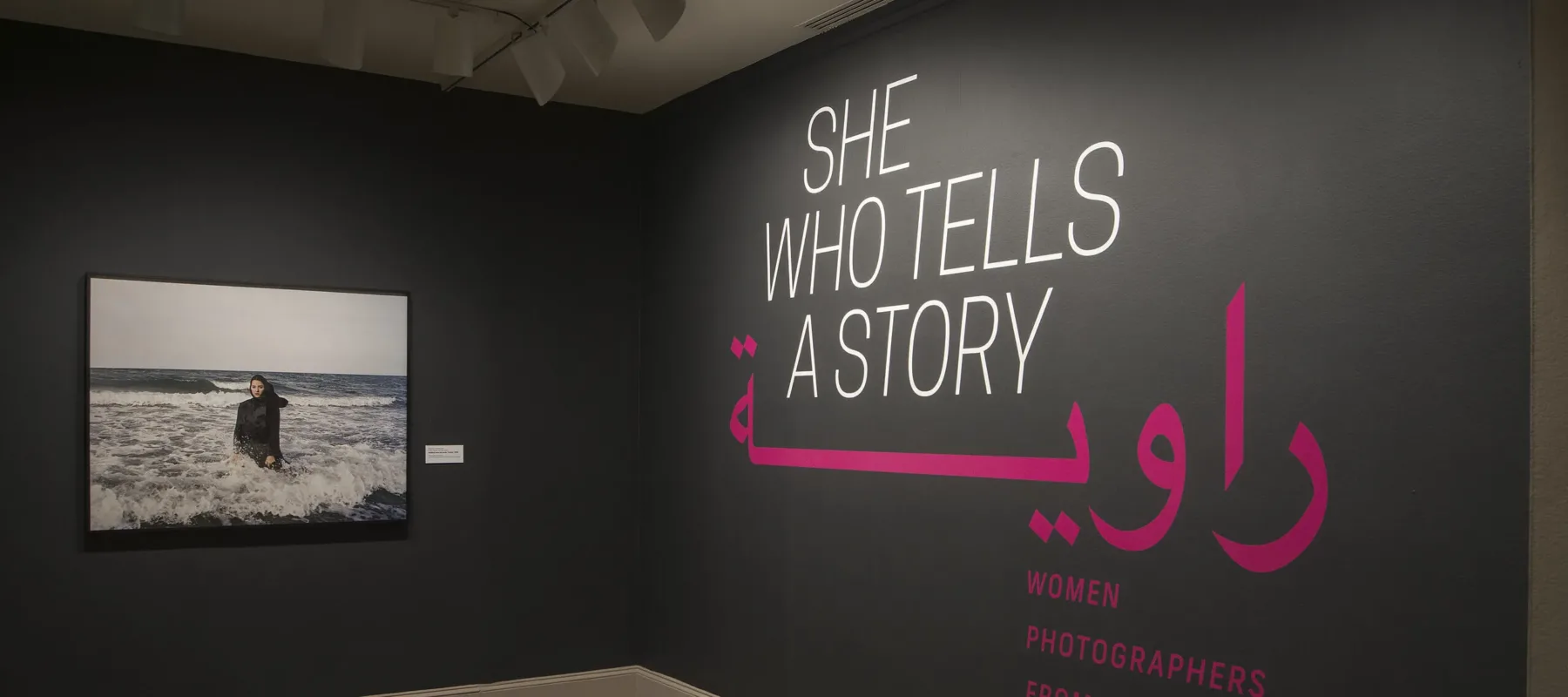

NMWA’s summer exhibition She Who Tells a Story: Women Photographers from Iran and the Arab World is organized around three themes: Deconstructing Orientalism, Constructing Identities, and New Documentary.

“Orientalism” refers to ideas about Eastern cultures that reflect Western fantasies and political priorities rather than reality. The 19th-century art movement established many artistic conventions that have had a lasting impact on how these regions (and their inhabitants) are portrayed.

The artists in She Who Tells a Story show an awareness of the influence of Orientalism on the representation of Iran and the Arab world.

By critiquing Orientalist artistic conventions, these artists forge a place for themselves as narrators of their own experiences rather than objects of fantasy.

Objectification of the Female Body

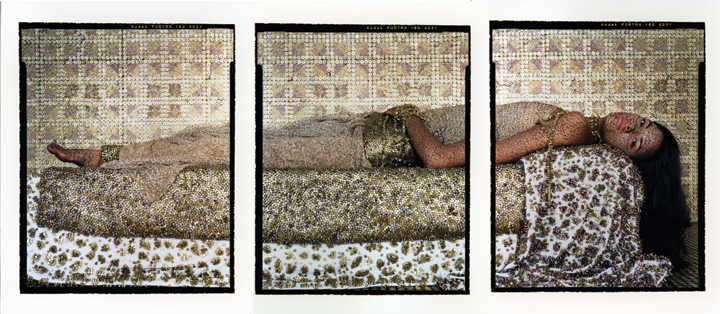

Many works in She Who Tells a Story examine the role of the female body in Orientalist imagery. Lalla Essaydi’s Bullets Revisited #3 reveals the inherent violence in objectified representations of women.

The triptych portrays a reclining woman covered with henna calligraphy and surrounded by bullet casings. The subject simultaneously entices viewers with beauty and confronts them with violence, signified by the bullet casings and fragmentation of the body. The photograph mingles violence and pleasure as the figure’s gaze confronts viewers.

Exotification and Imperialism

Artists also engage with the Orientalist tradition to reveal its political ties to imperialism. Rania Matar’s Mariam, Bourj al Shamali Palestinian Refugee Camp, Tyre Lebanon, from the series “A Girl and Her Room,” echoes the work of 19th-century Orientalist painters, whose popular works often showed idle figures in exotic but decaying settings.

Art historians have argued that this convention implies that the people portrayed are passive and morally deficient—a political message meant to justify colonization. The identification of the setting of this photograph as a refugee camp questions these assumptions by linking idleness and disrepair to war and displacement rather than moral failings. This, along with the subject’s direct and self-aware gaze, exposes the fallacy of Orientalist reasoning and redirects moral scrutiny onto the legacy of colonialism that continues to contribute to modern conflict.

From Object to Subject

The ongoing use of Orientalist imagery is a major concern for many of the artists featured in She Who Tells a Story. By deconstructing the political and visual conventions of Orientalism, artists like Lalla Essaydi and Rania Matar expose their violence and inaccuracy. The destruction of the Orientalist fantasy of Middle Eastern womanhood also allows for the possibility of female subjects: women who can see, think, create, and tell their own stories.