Sonya Clark: Tatter, Bristle, and Mend is intimate and deeply personal. It also is global, subversive, and steeped in the tradition of resistance.

Clark lures us in with beads and thread and hair: familiar, humble materials so exquisitely and unexpectedly crafted that one might miss the unsettling currents lurking just beneath the surface.

Each time I see Mom’s Wisdom or Cotton Candy (2011), the photograph of Clark’s slender pecan-brown fingers cradling a perfect sphere of her mother’s soft white hair, I feel the love and devotion they shared. But as with all of Clark’s creations, there is more than one interpretation. For those with curious minds and open hearts, there is political metaphor and cultural critique to be investigated.

Clark, with her visionary talent and sophisticated intellect, offers us an agenda beyond brilliance and beauty. Embedded in the exhibition is a narrative of what happens when people are enslaved, cultures subjugated, and continents vanquished. Clark’s works welcome questions, translate complex concepts, and confront white supremacy and the legacy of colonialism.

Through her lens, a strand of hair is love, beauty, joy, wisdom, pain, and the DNA from ancestors who were forcibly transported from Africa to the Americas. Sugar crystals represent her Trinidadian and Jamaican ancestors who harvested cane and the Europeans who grew rich from their labor. A Confederate flag is a symbol of hate that must be unraveled and reduced to impotent piles of red, white, and blue thread.

Sonya Clark and I bonded over our mutual interest in hair and its power in Black women’s lives. I knew I would learn from her when I heard her describe hairdressing as the first textile art form.

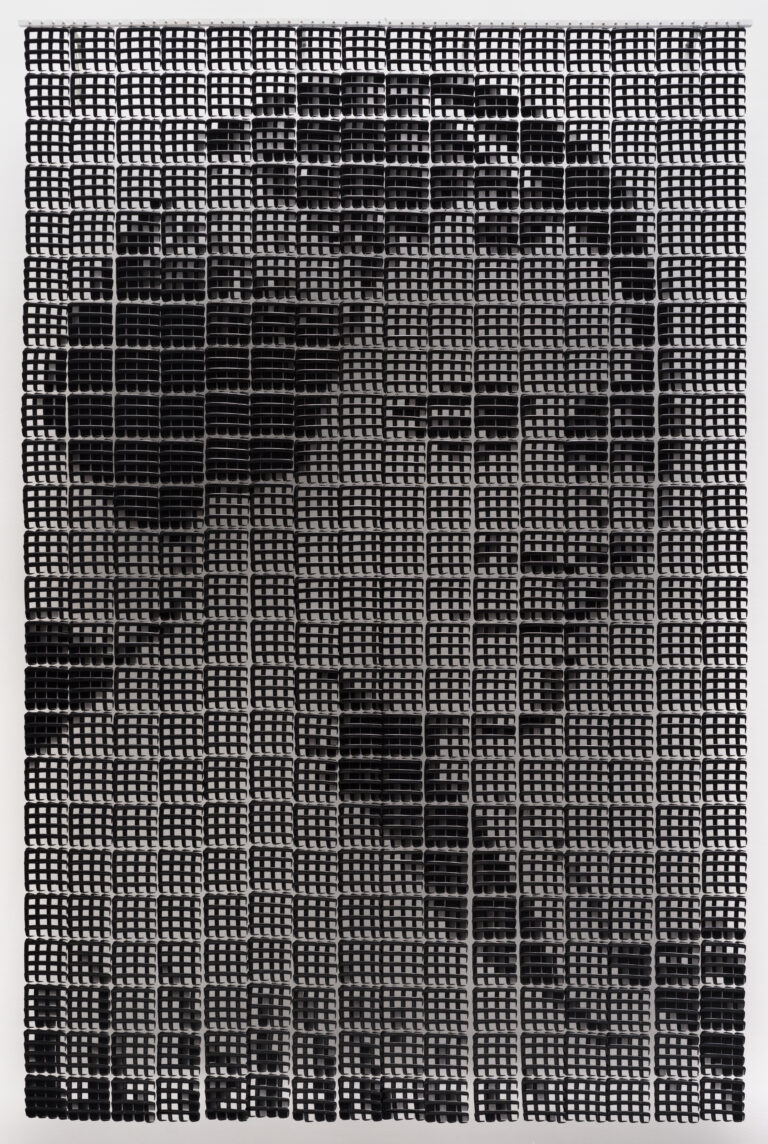

Around the time she created Hair Wreath (2002), her first sculpture made of human hair, she attended a book party for On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, my biography about my great-great-grandmother, the hair care entrepreneur. Then in 2008, she assembled Madam C. J. Walker, a massive 10-x-7-foot portrait.

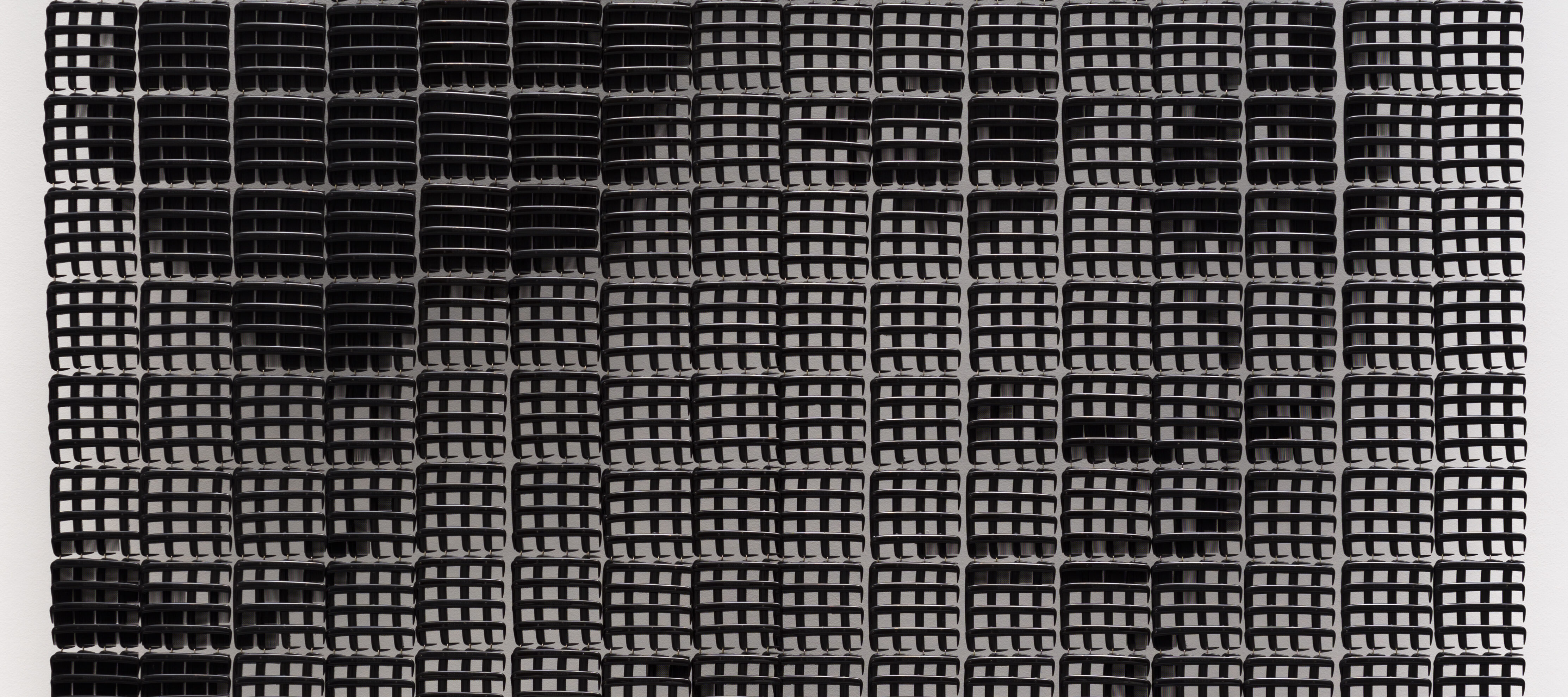

As always with Sonya’s work, what we see from a distance is both impressive and illusionary. What first appears to be a replica of Addison Scurlock’s iconic 1913 photograph of Madam Walker actually is 3,072 fine-toothed black, plastic pocket combs manipulated to form facial features, hair, and clothing.

I have been privileged to witness Sonya’s artistic journey during the last two decades and honored that my great-great-grandmother has served as muse and inspiration for some of her creations.

As I walked through Tatter, Bristle, and Mend, I was reminded that museums are protected, orderly spaces. But here the security guards, most of them Black, had proudly assumed the role of docents and guides. As we all basked in the embrace of Sonya’s work, I knew I was in a place where the artist understood me and where I could hear her inciting resistance and whispering revolution in a hushed, gallery-appropriate manner.