Through collaborating with a research team from the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) and delving beneath the surfaces of two paintings by Alma Woodsey Thomas (1891 to 1978), NMWA gained vivid new insight into beloved works by a Washington, D.C., artistic icon.

Conservators from the Lunder Conservation Center at SAAM visited NMWA in 2019 to examine two paintings in the museum’s collection by Thomas. Led by Amber Kerr, chief of conservation at SAAM, conservators undertook their study of Thomas’s art in preparation for an upcoming exhibition of her work organized by the Columbus Museum in Georgia and the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia. An exhibition scheduled to open at SAAM in 2021 prompted Kerr and her team to examine and plan treatment for several works, and they decided to dig deeper. They reached out to NMWA as well as other institutions, including the National Gallery of Art, the Baltimore Museum of Art, and The Phillips Collection, to look closely at additional examples.

The researchers performed multispectral imaging of the paintings Iris, Tulips, Jonquils, and Crocuses (1969) and Orion (1973). Through this safe method of measuring light at different spectral channels, they hoped to learn more about Thomas’s work process. They shared imagery and some initial findings from their peek below the paintings’ surfaces.

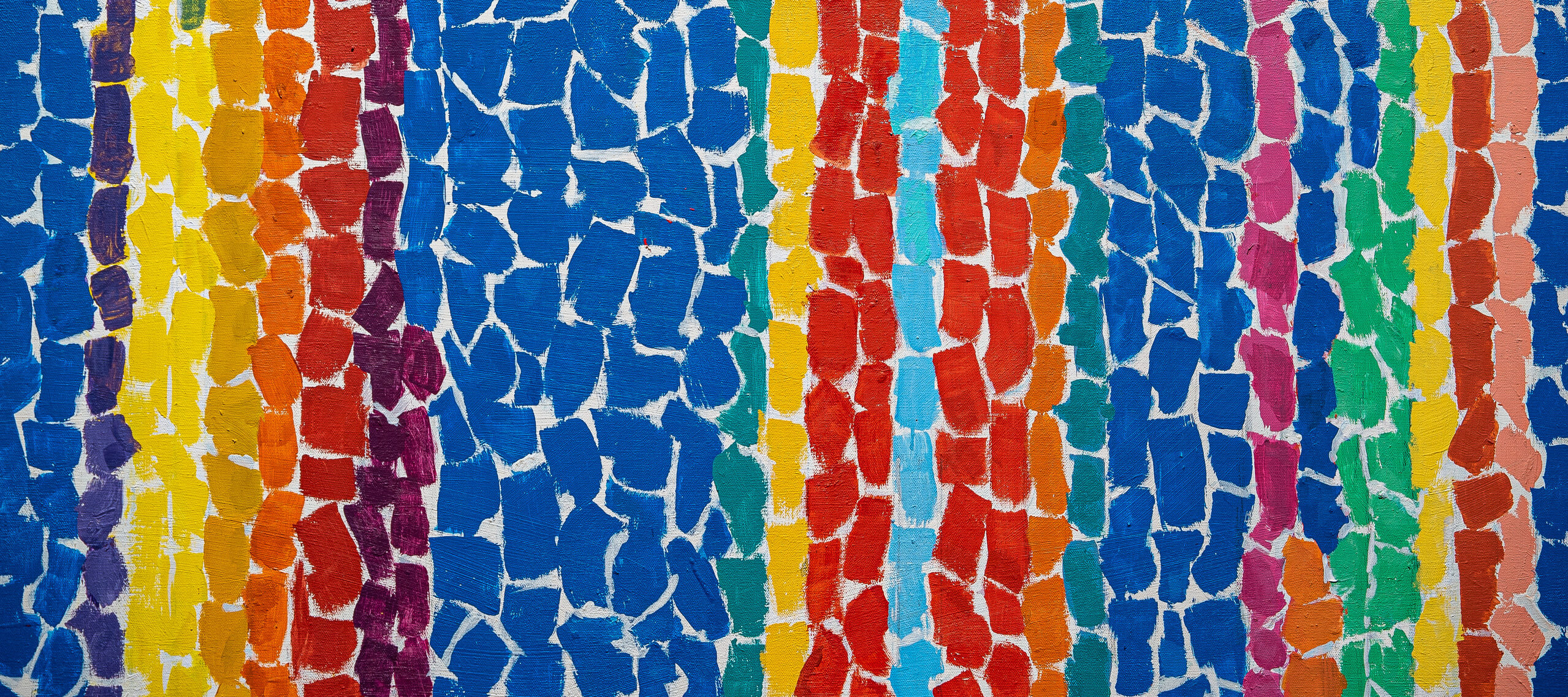

Thomas gained renown late in life for a signature abstract painting style featuring colorful rows or circles of lozenge-shaped brushstrokes. She emphasized nature as her primary source of inspiration. Titles such as Iris, Tulips, Jonquils, and Crocuses reflect her never-ending fascination with the colorful interplay of flowers and other natural phenomena outside her window. Orion, named for the constellation, is part of a series of paintings sparked by her wonder and enthusiasm for space exploration.

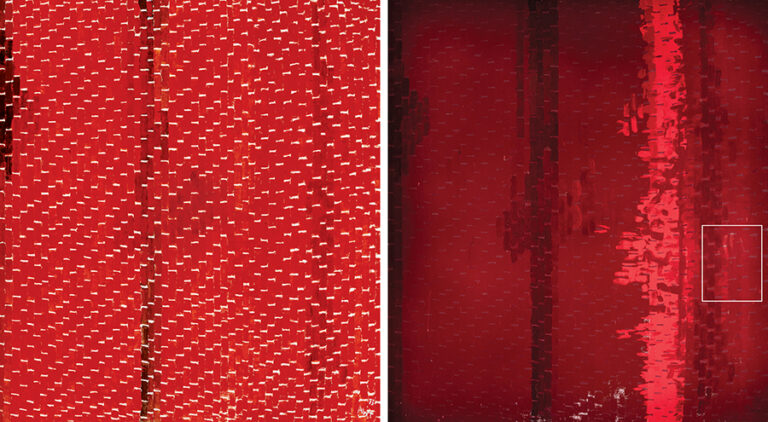

One aspect of Thomas’s process that piqued the conservators’ curiosity was her use of guiding pencil lines. Many of her works in this style, the artist’s so-called “Alma stripes,” show faint graphite lines that Thomas placed on her canvases, providing a structure for her colorful marks. To investigate her use of pencil lines, the conservators used infrared reflectography to differentiate carbon-containing mediums, like graphite, from other art materials. They found distinct lines in one work: “In developing Iris, Tulips, Jonquils, and Crocuses, Thomas charted each section of color by scribing the vertical lines with a sharp graphite pencil…[indicating] the use of a straight edge.”

A second technique the conservators used was ultraviolet (UV)-induced luminescence, which can cause certain materials to “‘fluoresce’ and emit light,” the researchers explain. This exposed an unexpected and powerful sign of the artist’s presence: a partial handprint glows on the surface of Orion. The research team believes that this “may be an artifact of Thomas contacting the work (possibly for support) while her hand was coated with red-lake paint, during reworking of the fluorescing sections.”

Many details of artworks are invisible to the naked eye. For these paintings by Alma Woodsey Thomas, collaboration and examination illuminated their fascinating history.