Alma Woodsey Thomas (1891–1978) is currently the subject of a comprehensive survey exhibition, Alma W. Thomas: Everything is Beautiful, on view at Washington, D.C.’s Phillips Collection through January 23, 2022—and traveling to several venues over the coming months. Through the extensive holdings of the Columbus Museum, which houses much of Thomas’s early-career art and archives, the exhibition contextualizes the artist’s well-known later paintings alongside her early works and those of her circle of artistic friends and influences.

Everything is Beautiful

An important aspect of Alma W. Thomas: Everything is Beautiful lies in the curators’ efforts to situate Thomas in relation to other artists in Washington, D.C., from the 1930s through the ’70s. While the Thomas paintings in NMWA’s collection are not in the exhibition (they are traveling with the exhibition Women in Abstraction at European museums this summer and fall), the museum loaned two works by contemporaries of Thomas: Loïs Mailou Jones (1905–1998) and Céline Marie Tabary (1908–1993). Jones is represented in the exhibition by her landscape painting Arreau, Hautes-Pyrénées (1949), and Tabary by the lively scene Terrasse de café, Paris (Café Terrace, Paris) (1950).

Both Jones and Tabary, like Thomas, lived and worked in D.C. and were active in the city’s thriving art scene. Jones began teaching art at Howard University in 1930 and trained artists including David Driskell, Elizabeth Catlett, and Sylvia Snowden. During her first sabbatical year from Howard in 1937, Jones received a fellowship to study at the Académie Julien in Paris. It was there that she met Tabary, also a student at the academy, who was initially assigned to be Jones’s translator. As the African American Jones and white French Tabary painted side by side along the Seine, the pair formed a lifelong friendship. Tabary came to D.C. in 1938 to visit Jones and, due to the impending war in Europe, stayed on and eventually joined the art faculty at Howard.

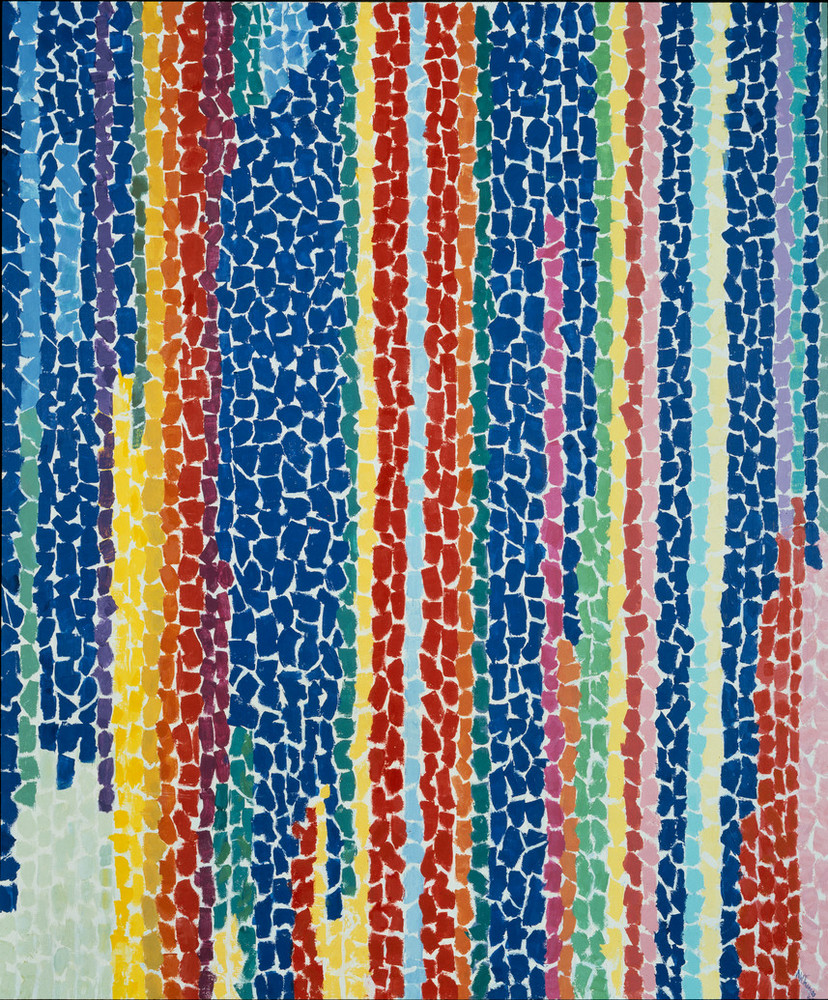

In segregated Washington, D.C., Jones and Tabary saw the need for a space for artists of color to gather, show their work, and share ideas. In 1948 the pair opened “The Little Paris Studio” in the attic of Jones’s home in the Brookland neighborhood. Thomas frequented this “salon,” and many of her early works display the same post-Impressionist influence that characterizes the works of Jones and Tabary.Thomas, however, became increasingly interested in “creative painting,” and eventually left the group, which she felt was too attached to realism. This path ultimately led her to her innovative later style and works such as NMWA’s Iris, Tulips, Jonquils, and Crocuses (1969) and Orion (1973).

Alma W. Thomas: Everything is Beautiful expands its reach to demonstrate that Thomas consistently honed her skills and experimented within her artistic practice during the earlier part of her life. Works like Jones’s and Tabary’s help to tell the story of Thomas as a part of the artistic fabric of Washington, D.C., in the mid-20th century—and likewise show how she set herself apart.