At the National Museum of Women in the Arts, we regularly rotate our collection to spark new thematic connections. This is an essential part of our curatorial philosophy. In a six-post series, I will explore the themes featured in our most recent collection installation. Read about our “Family Matters” and “Rebels with a Cause” themes, and stay tuned for more.

Spaces, both physical and metaphorical, often have strong gendered associations. Historically, conventional ideas about women’s purportedly delicate sensibilities led them to be regularly restricted to private, interior environments—sites of protection and confinement. Such isolation limited women’s active participation in the exterior, public realm directed by men.

Many women artists evaluate the complex interrelationships of inside/outside and the female body. Employing imagery and materials that frame, envelop, or reflect the body, they reconfigure our assumptions about personal space.

Gallery Highlights:

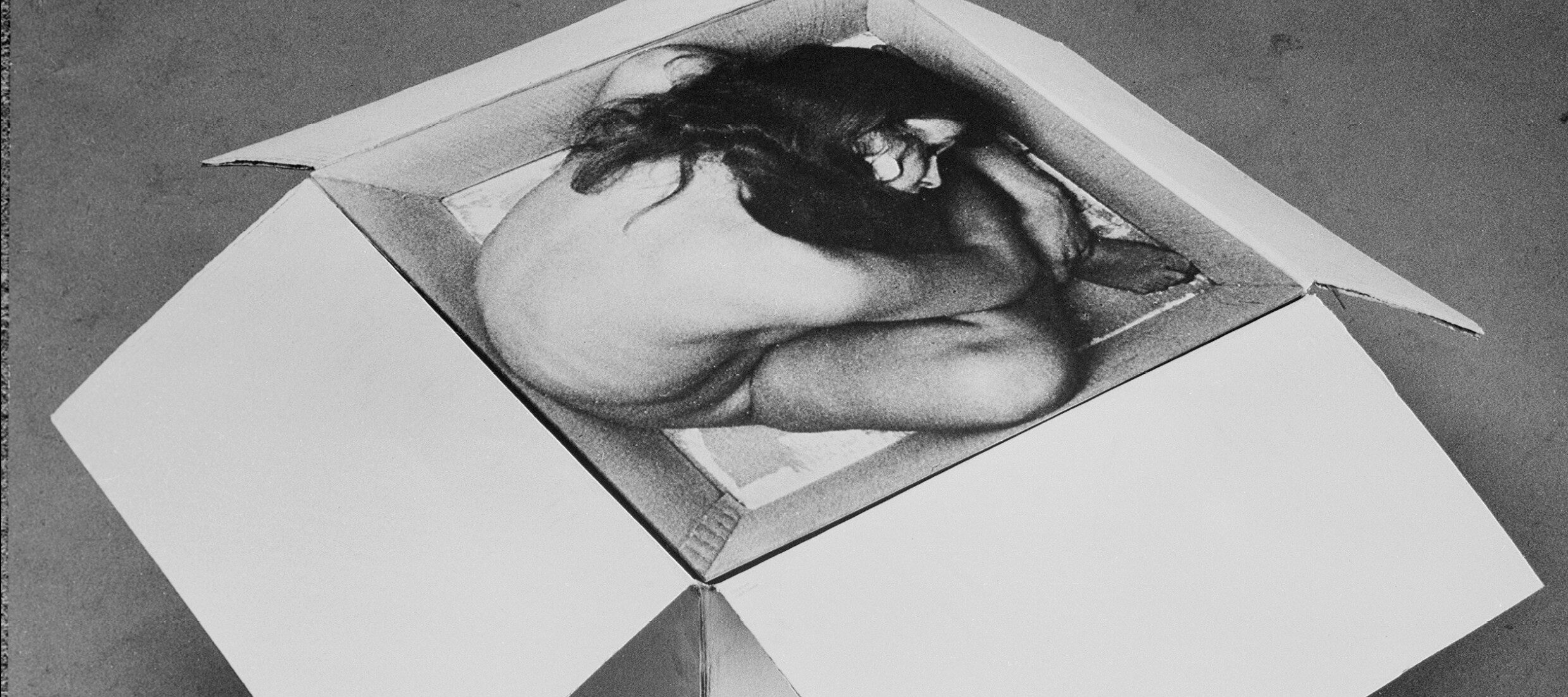

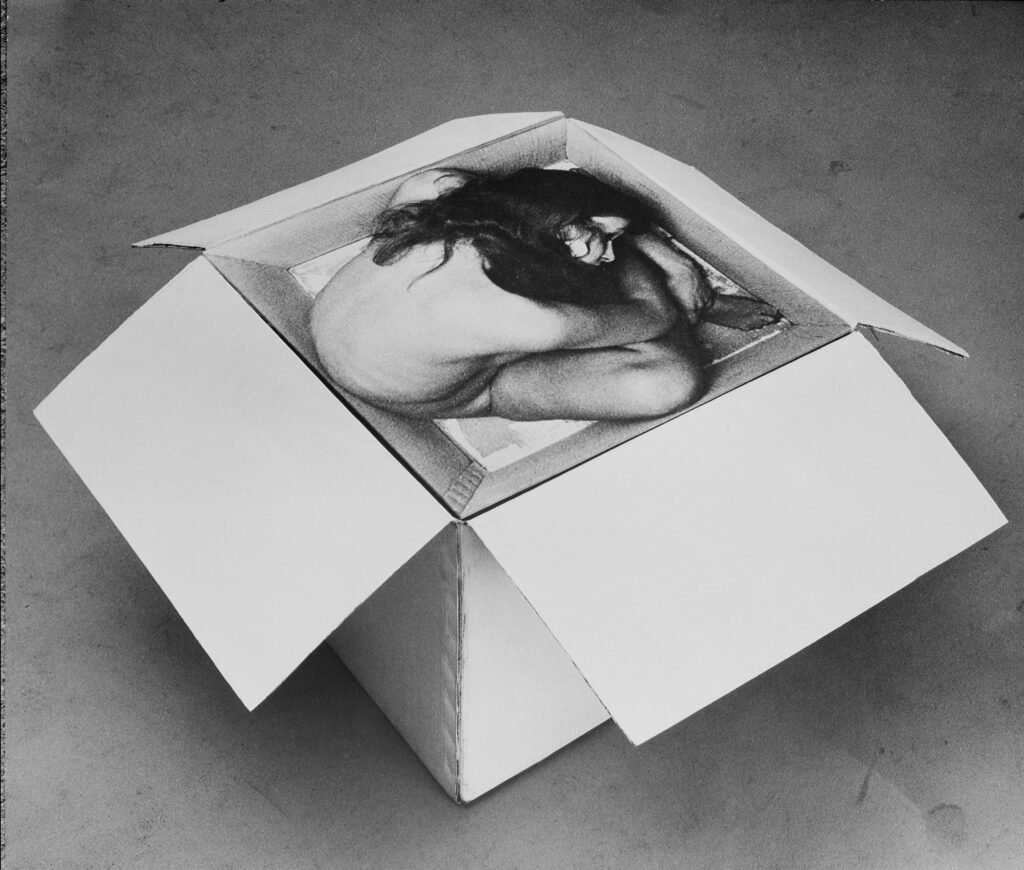

Body-art pioneer Kirsten Justesen subverts the conventional approach to sculpting the nude female figure. For centuries, artists positioned figurative sculptures atop a plinth in order to provide the viewer a 360-degree view. Justesen’s compelling Sculpture II (2010), a remake of an object she first created in 1968, upends this tradition. The piece comprises an open cardboard box that reveals a photograph of the artist’s own curled body. This image of a woman in a box disrupts the viewer’s voyeuristic perspective and, perhaps, provides commentary on social constraints imposed upon women.

Dutch photographer Hellen van Meene also depicts a woman in a confining situation. In her photograph Untitled (68) (1999), she positioned her model in a domestic space: hidden beneath the cushions of a living room sofa, like a child at play. The pillows envelop the woman, who rests with her eyes closed, and suggest both containment and comfort.

With her back to the viewer, the figure in Alison Saar’s print Mirror, Mirror: Mulatta Seeking Inner Negress II (2014) is also somewhat concealed, her face visible only through her reflection in the frying pan she holds. The figure and the print’s title evoke the fairy tale Snow White, which contains themes of female self-critique and a culturally narrow standard of beauty.

[URISP id=15378]

Although she worked more than a century before these contemporary artists, impressionist Berthe Morisot created a deceptively serene view in her painting The Cage (1885). She applied paint in vigorous strokes on an unprimed canvas to depict a pair of caged love birds. Huddled close together and positioned beside an exuberant vase of flowers, the birds appear diminutive and vulnerable.

Decades later, photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe also used the bird cage. Rejecting studio settings and mannequin-like poses, she brought a formal precision and an irreverent sense of humor to the fashion magazine Harper’s Bazaar from 1936 to 1958. Natalie with Bird Cages (1950) depicts a woman standing between two bird cages, seemingly at ease and assured—and by no means confined or caged herself.

These and other works in “Space Explorers” showcase how elements of architecture, mirrors, and other objects highlight the physical and psychological nuances of enclosure.