Textile and social practice artist Sonya Clark (b. 1967, Washington, D.C.) transforms common objects into works that probe identity and visibility, appraise the force of the African Diaspora, and redress history. She stitches, braids, unravels, and weaves recognizable materials such as human hair, plastic combs, glass beads, and flags. Now on view, the midcareer survey Sonya Clark: Tatter, Bristle, and Mend features approximately 100 works of art. It is the first exhibition to consider the artist’s capacious body of work, created over more than two decades.

Learn more about the exhibition’s themes below and plan your visit to experience it in person through May 31.

The Primordial Textile

Much of Clark’s work concentrates on the head and hair, demonstrating her embrace of the Yoruba principle that alignment of the consciousness and spirit occurs through the head. She credits cultural critic Bill Gaskins with the observation that “hair is the primordial textile.” She also notes that a strand of hair possesses a person’s whole DNA sequence, standing in for a body and an extended genealogy. Hair Necklace 3 (2012), a long, dark-colored dreadlock that grays near its end, combines the hair of Clark and her mother into a single, rolled lock, connecting their DNA and ancestry.

With a Fine-Toothed Comb

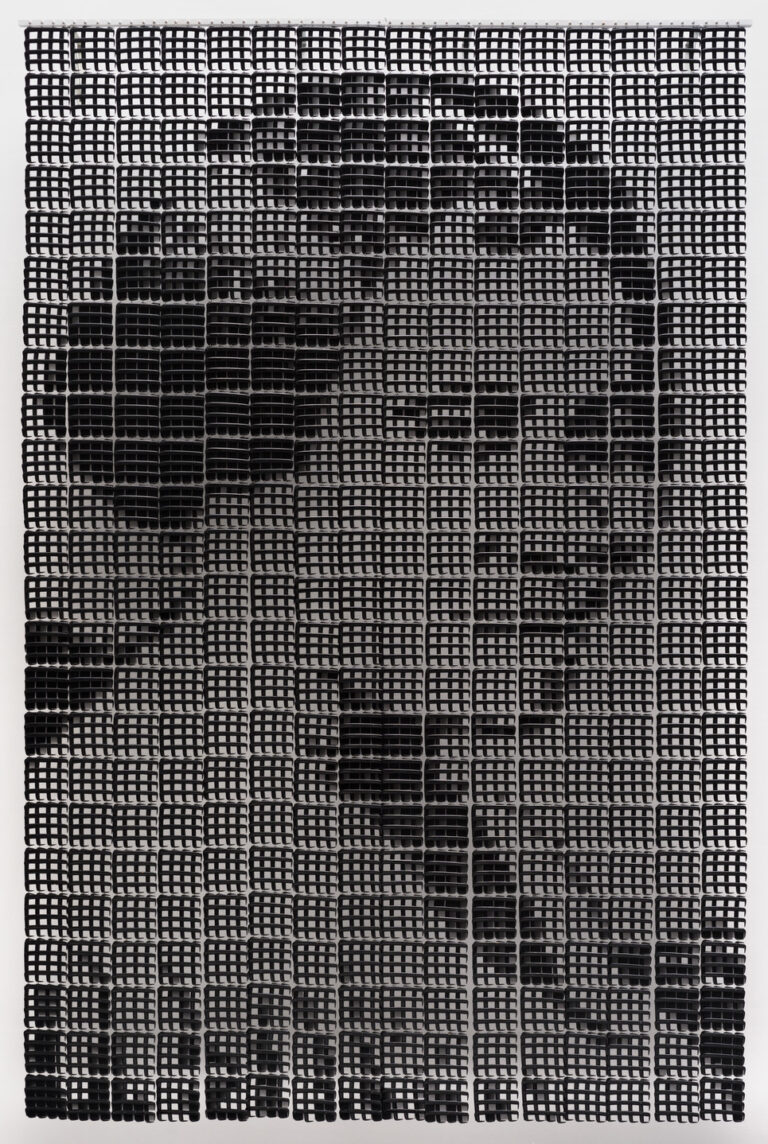

In works like Lexie’s Curl (2008), Clark builds larger-than-life hair coils from plastic pocket combs, a tool that cannot tame them. In other works, Clark snips away individual teeth to create shade and depth that reveal patterns and images. Madam C. J. Walker (2008) pays homage to America’s first female self-made millionaire, who built an empire of Black hair care products.

Unraveling Invisibility

Clark recently began an expansive body of work related to the obscure truce flag, a white cotton dishcloth edged with three thin red stripes that was used by Confederate troops to surrender at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865, marking the end of the American Civil War. Clark’s evocative works related to the American presidency and the Confederate battle and truce flags challenge viewers to question their received beliefs about these symbols.

Triangulation

With ancestral roots in Jamaica, Trinidad, Nigeria, and Scotland, Clark explores the connections among Africa, the Caribbean, Europe, and her own family through works that allude to the sugar trade, and thereby the transatlantic slave trade. A recent group of sculptures incorporates sugar and gold directly. Clark creates delicate sugar flowers nestled amid dried cotton burr in Cotton Candy Flower (2016) and crowns gold Engagement Rings (2016) with “stones” of sugar.

Prayer Beads

Intricately woven and beaded headpieces, among Clark’s earliest works from the 1990s, interpret African customs of adornment. Built from thousands of tiny, glimmering glass spheres, other beaded sculptures depict hands, outstretched arms, and chromosomal strands, ethereal manifestations of familial and ancestral bonds.

This exhibition affirms Clark’s prowess as a maker, historian, and visionary. Her work demonstrates not only her keen ability to expound on a subject, but also her intuitive understanding of how the present unwinds from the past and twists through to the future.

Can’t visit in person? Check out the online exhibition, listen to an audio guide, and buy the fully illustrated catalogue.