For centuries, women photographers have ventured outdoors, exploring environments and investigating natural forms that inspire close examination of our own surroundings. Though women were involved in the development and advancement of photography from its origins in the 19th century, their contributions received little attention until the late 1970s.

Today, grappling with a period of global quarantine, many people are experiencing an urge to return to the outdoors, seeking comfort and revitalization in nature. Return to Nature, a pop-up installation showcasing a selection of historical and contemporary photographs from NMWA’s collection, illustrates artists’ longstanding fascination with the natural world. From dreamy, lush landscapes to more minutely detailed botanic studies, Return to Nature offers a much-needed moment of escape and a reminder of the renewal that occurs in nature and in ourselves.

Learn about the life and work of several artists in the installation below, and schedule your visit to the museum to see these works in person alongside photographs by Justine Kurland, Louise Dahl-Wolf, Mwangi Hutter, Rineke Dijkstra, and others.

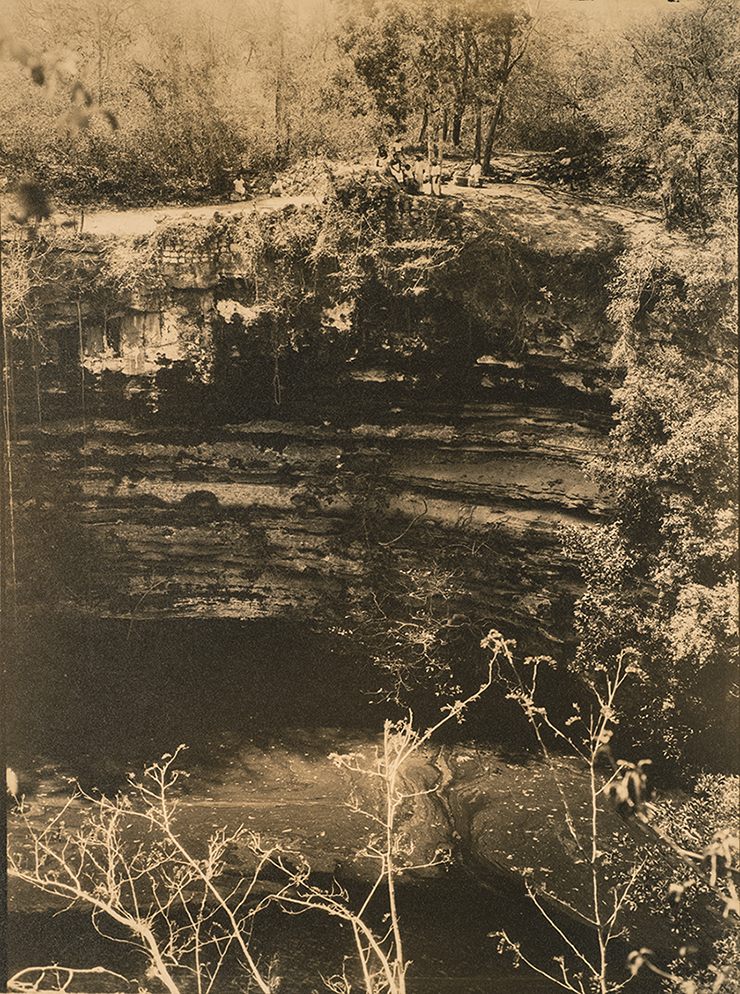

In 1932, Laura Gilpin (1891–1979) took her first of three trips to the ruins of Chichén Itzá, a large Mayan city in Yucatán, Mexico. Known for prioritizing mood over image sharpness, she wrote of the difficulty in retaining the “austere and barbaric qualities” of the great temples. In Group by the water (The Sacred Well, Chichén Itzá) (1932), she captured a large sacred well overgrown with plant life. While the massive structure fills most of the frame, at the top of the composition Gilpin catches a group of visitors to the site. The presence of these minute figures allows a sense of scale, revealing the magnitude of the structures created by the ancient civilization.

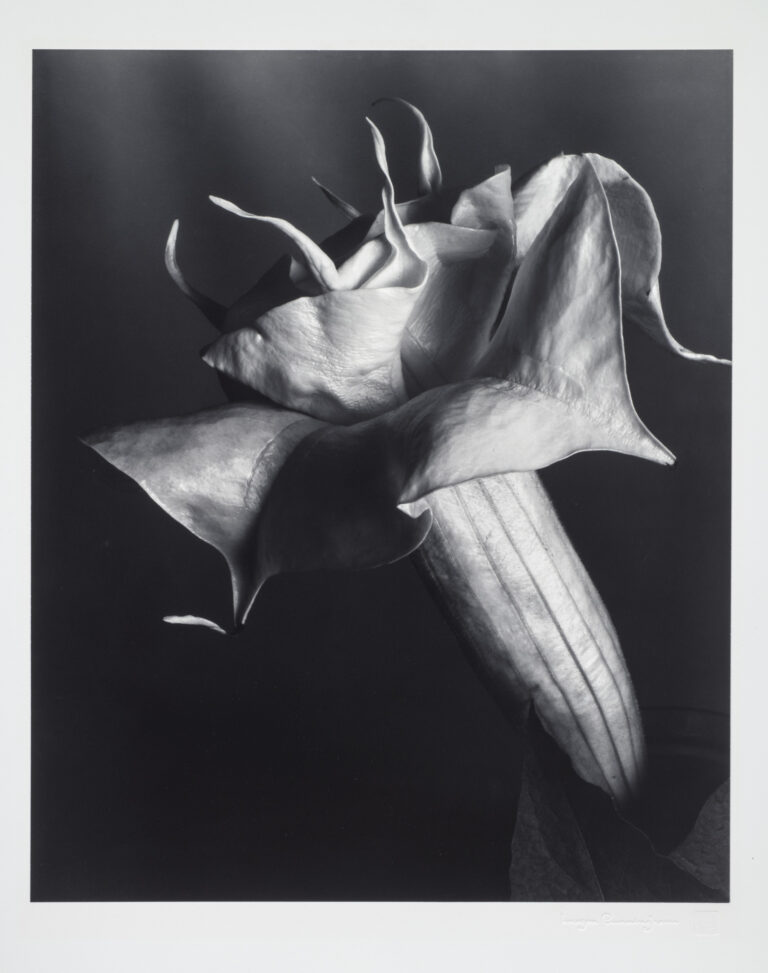

Imogen Cunningham (1883–1976), one of the first professional women photographers in America, helped found Group f/64, an association of West Coast photographers who adopted a style of photography that favored sharp focus and exaggerated value contrast. Her intimate floral still lifes resulted from in-depth, sometimes years-long, studies of specific flowers. With Datura (ca. 1930), Cunningham’s skillful handling of light and contour capture the shape and texture of each petal in sensuous detail. Photographed in profile and set against a blank, dark background, the floral subject receives the same meticulous consideration Cunningham gave to her human portraits.

Amy Lamb (b. 1944) pursued photography after a career in molecular biology. Trading her microscope for a camera, Lamb explores the natural world in vivid detail with her floral portraits. Like Cunningham, Lamb carefully considers light, form, and texture, but color is another important element to her photography. Lamb’s Purple Datura (2015) captures the bloom at its peak—an explosive, bright violet form that reveals the ripples, folds, and curves of each petal. “Flowers reveal forms, structures, and patterns that suggest an inherent harmony with the universe,” the artist says. “Form and symmetry in the plant world are inherently beautiful. Every plant seems to portray a new interpretation of the predictable patterns of nature.”